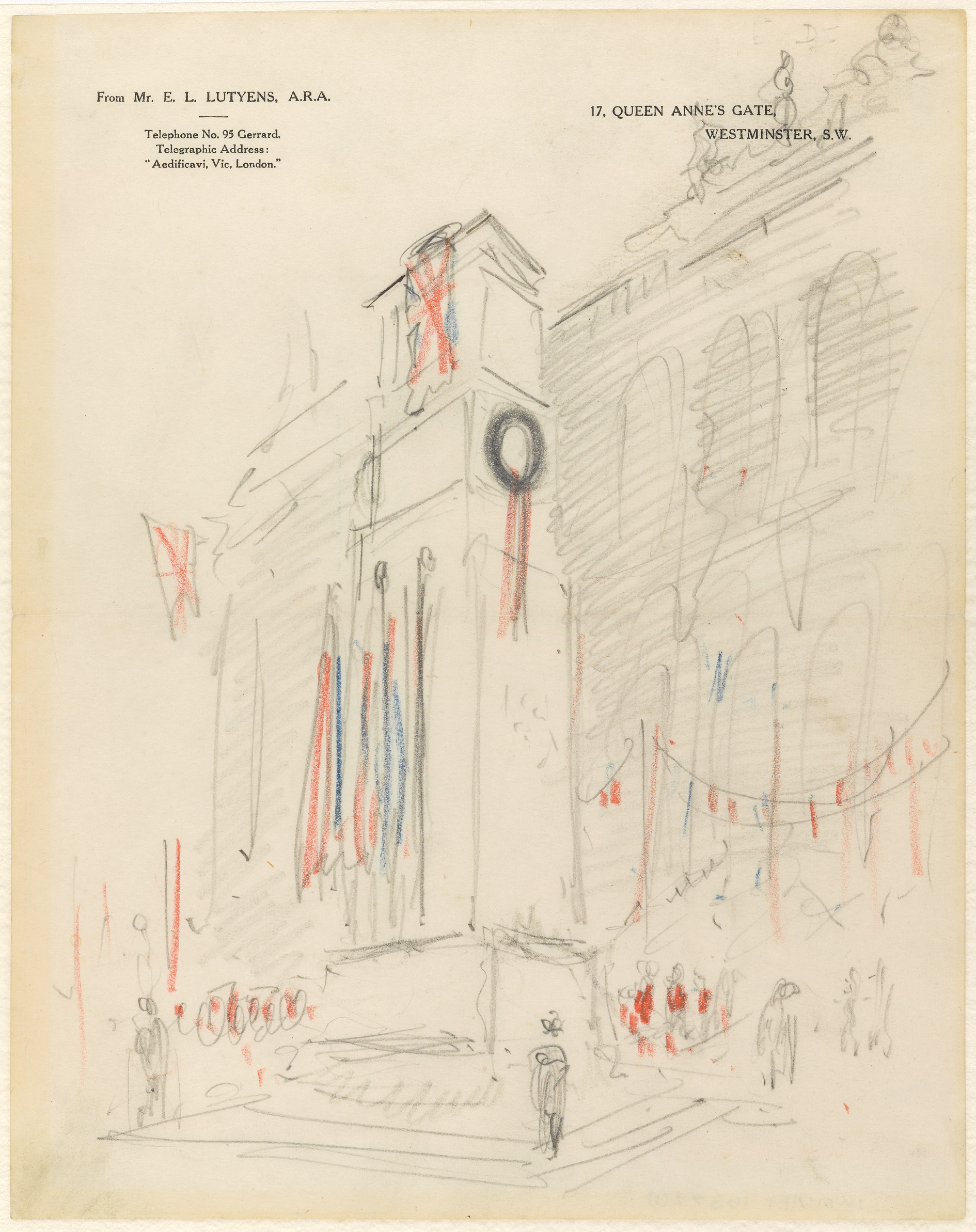

A Lutyens sketch of the Cenotaph — imagined during a Remembrance ceremony — on his office’s letter- headed paper. Courtesy of Imperial War Museums

The unveiling of the permanent version of the Cenotaph, in Portland Stone, November 11, 1920 © Imperial War Museums. This day also witnessed the burial of the Unknown Warrior

The Cenotaph in 1919 (© The National Archives), originally intended only to be a temporary structure for a one-off parade, and made from wood and plaster

We Will Remember Them: London’s Great War Memorials Exhibition

By Mervyn Miller

This exhibition, appropriately shown at Wellington Arch at Hyde Park Corner, has been assembled by English Heritage to provide a narrative to the six London war memorials under its care. The exhibits are of the highest significance in evoking diverse and sensitive responses to the sacrifice of the First World War, which caused 1.1m fatalities in Britain and the empire. What is most striking is the lack of triumphalism, not only in these six, but also in the countless others spread across the UK. Although figurative sculpture of the highest quality is often present, the abstract values of geometrical concepts underlie many memorials, creating a symbolism of eternal sacrifice. I’ve decided to focus on three of the six.

The Cenotaph is undoubtedly the most profound, and was designed by Edwin Lutyens in temporary form in July 1919 to evoke a national tomb as the focus of a commemorative parade of veterans. Its wood and plaster incarnation was so popular that the government resolved to pay for a permanent memorial in which Lutyens deployed the subtle refinements of entasis, as used on the Parthenon, to enhance its inherently symbolic values of eternity. Original sketches — one ‘sketched at dinner’ — show how the design sprang to life, while already hinting at its final form from its creator’s inexhaustible reserves of creativity. Alongside are large photographs of the temporary version and the permanent one, unveiled on Armistice Day in 1920, shortly before the procession of the unknown Warrior passed en route to ceremonial interment in Westminster Abbey. It’s a great pity that the Cenotaph material is displayed on the staircase, which makes its study very difficult, but there are riches at every turn. Cenotaph reproductions of widely differing quality — including in the shape of a money box — show how the memorial captured the public’s imagination in the interwar period.

Elsewhere, highlights include maquettes of two sculptural masterpieces by Charles Sargeant Jagger — of a British soldier reading a letter from home for the Great Western Railway Memorial at Paddington Station and The Driver, part of the Royal Artillery Memorial for which Jagger (who served on the Western Front) also carved relief sculptures depicting different forms of artillery warfare. The blocky form of the latter’s Portland Stone base by the architect Lionel Pearson supports a bronze howitzer, while mute figures stand against the plinth between the carved panels with a bronze of a dead gunner laid out on the base of the north end. This sublime memorial, unveiled in 1925, has been superbly restored, and can be viewed from the balcony of the summit of the arch.

The nearby Machine Gun Corps Memorial, also unveiled in 1925, commemorates ‘the suicide club’ of the Western Front. It was designed by Francis Derwent Wood, and surprisingly features a naked figure of David — a vulnerable renaissance beauty holding Goliath’s sword, having slain him, and flanked by the brutal realism of replica Vickers Mark I machine guns (real ones clad in bronze) thrust through laurel wreaths. supporting artefacts include a maquette for David and a photograph of Wood painting prosthetic face masks for disfigured soldiers.

The cramped exhibition space means that it is best to visit at off-peak times, but do see it: it’s a case of compressed excellence, and a way of viewing Lutyens’s best-known war memorials in the context of work by distinguished colleagues.

We Will Remember Them: London’s Great War Memorials is at Wellington Arch, Hyde Park Corner, London W1J 7JZ until 30 November, 2014