Groote Schuur

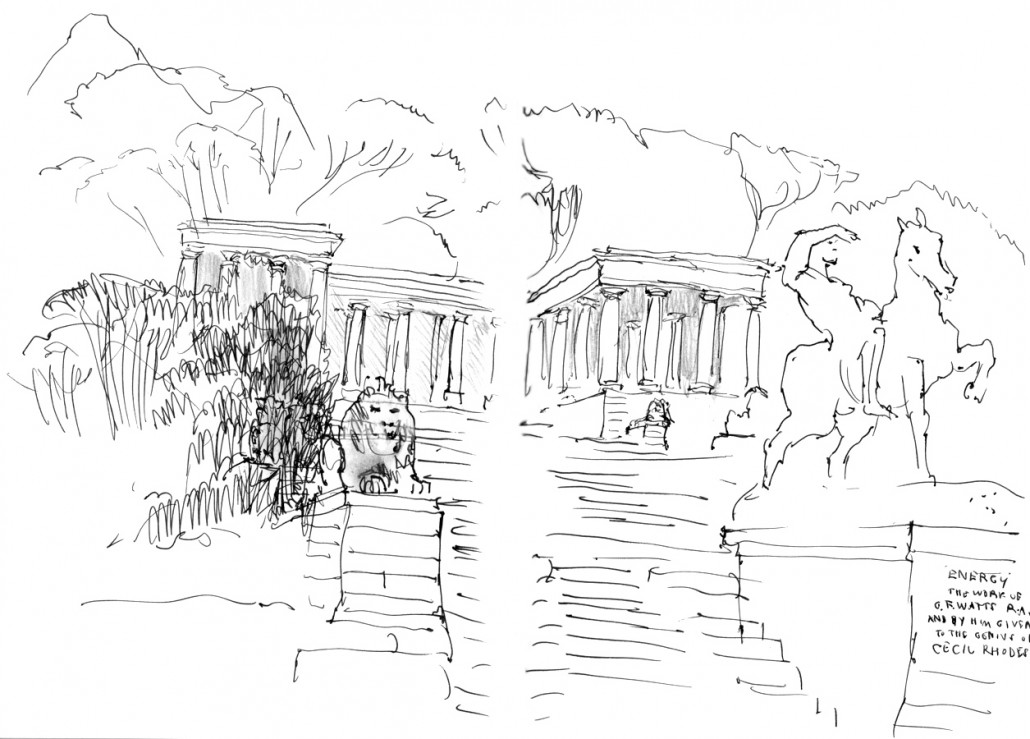

Rhodes Memorial illustrated by Andrew Wilton

Rhodes Memorial

Thoughts on a Visit to Groote Schuur

by John Comins

There seems to be no record of the precise instructions, if any, given by Cecil Rhodes when in 1892 he commissioned Herbert Baker to re-model Groote Schuur, the Great Barn, outside Capetown. It is known that Rhodes was attracted to Cape Dutch architecture, and it may be that he wished to point up the continuity of British rule with the Dutch inheritance of the Cape. At the time there was a general perception that Rhodes and Baker had together led a revival of the Cape Dutch style. Certainly, Groote Schuur established a vogue for a new architectural approach that dominated domestic building in South Africa for more than a generation.

The paradox is that what Baker gave Rhodes differed very markedly from traditional Cape Dutch buildings. “Teak and whitewash”, Rhodes’s words for the decoration he preferred, they certainly had, but a Cape Dutch house owner of the 1800s would have been amazed at the transformation affected a century later. The opportunity to compare a number of Baker’s South African houses with earlier buildings yielded ample evidence that Baker like Lutyens struck out on his own path. In no instance that we saw had Baker attempted precisely to replicate earlier styles, but paid them graceful tributes by including in his repertoire a number of genuine Cape Dutch features.

At Groote Schuur, the profuse application of “Dutch” gables and the two great stoeps nodded vigorously towards the Cape tradition. To these were added bulls eye and half round windows, relics of the earlier English rebuild, half shutters to the ground floor windows, barley sugar chimneys, and elaborated gable decoration all seemingly well outside Cape Dutch precedents.

What we find at Groote Schuur is an Arts and Crafts architect seizing his chance with Rhodes’s backing to introduce to his new country a new style; a blend of inherited Cape architecture with the contemporary English country house and assembled with rare self-confidence and panache. Indeed one of one’s lasting impressions of the house is wonder at the assurance and conviction of the 29 year old architect. The practice of George and Peto did not discourage individual thinking in its acolytes.

For Rhodes, the house had to serve many purposes; an environment congenial to the discussion of politics and statecraft, a place for private entertainment and, on occasion, the grandest social gatherings. It had also to be appropriate to the political stature of its owner, then Prime Minister of the Cape and an acknowledged prime mover in the affairs of the continent. Baker despite his relative inexperience understood this perfectly. The house is not without elements of grandeur but these are softened by the intimacy and domesticity of a small country house.

The entrance front sounds the grand note. It has nine bays, wings headed by two large gables linked by a stoep with Ionic columns, and complemented by a further smaller central gable. Steps lead up to the massive front door translated from another Cape house. Set back from the left hand wing are the large service quarters, taking up as much space, if the billiard room is included, as the main house. Imposing as it is, it can be argued that this façade is the least satisfactory feature of Baker’s creation. The service wing is too intrusive and hardly subservient to the main quarters, and the detailing of the front with its unhelpful central sculpture seems cluttered and over ornamented. It is interesting that Baker’s pre fire version of the house lacked half shutters to the ground floor windows, an omission which improved the overall appearance.

The garden front is dominated by the stoep which supported by no less than 12 Tuscan Doric columns, runs along its whole length. It looks directly out on to the terraced borders, the giant stone pines and the almost oppressive mass of Table Mountain; the mountain which had first attracted Rhodes to the house.

The drawing room, dining room, library, and two ante-rooms are outweighed by the space devoted to the front and back stoeps and the hall and vestibule. It might seem to be under equipped with reception rooms until one remembers the contemporary use of hall space for social purposes, and the immense garden stoep which was Rhodes’s favourite space for relaxation and entertainment.

The mass of matured and finely carved wood dominates the interior. Panelling, columns, floors, doors, chests and armoires mostly in Burmese teak create with the relatively low wooden ceilings a simple but sumptuous atmosphere, which might become oppressive if it were not relieved by the long windows, the displays of blue and white porcelain and the charming and inventive brass door furniture.

The house is now devoted to State entertainment and accommodation and access is very strictly controlled. Rhodes’s cherished domestic atmosphere may have vanished but the property is beautifully maintained and its immediate surroundings remain largely unchanged. The mind’s eye can still imagine Rhodes at his ease on his garden stoep while his servants, lacking all musical skills, serenade the company

to his satisfaction and to the horror of his guests.

John Comins