The Architecture of Sir Ernest George: Book Review

by Hilary Grainger

This study of the life and work of Sir Ernest George (1839 -1922) is long overdue especially for those with an interest in his most famous articled clerk, Sir Edwin Lutyens (1875-1944). In the late nineteenth century domestic architecture in England was dominated by the office of Richard Norman Shaw, closely followed by that of Ernest George; the young Lutyens had hoped to enter the office of Shaw, but instead joined George’s practice in 1887, where he stayed for just over a year. He learnt much and met the cream of young architects, among whom were Herbert Baker, Guy Dawber and Robert Weir Schultz. Monographs on Shaw appeared long ago, Reginald Blomfield’s in 1940 and Andrew Saint’s acclaimed study in 1976; the work of Edwin Lutyens was commemorated immediately after this death and the Arts Council Exhibition of 1981 led to an enthusiastic revival of interest in his work. Hilary Grainger’s elegantly written and beautifully produced book, published by Spire Books with new photography by Martin Charles, is another piece placed in the jigsaw of architectural history which takes us into the building world in the late 19th century, indeed until 1914 when work came to a grinding halt.

Ernest George’s private and professional lives were impeccable. He married in 1866 and was widowed ten years later when his wife died in childbirth; his unmarried sister Mary joined his family to help him raise his seven children in Redroofs, a house he designed for himself on Streatham Common. George was a collector of considerable taste and the interiors of Redroofs showcased his talent, and mirrored the aspirations of his clients. The same taste was to be found in his office at Maddox Street. It was only in 1903 he moved to central London after his children had left home.

George could have pursued a career as a very successful water colourist but he chose to devote his professional life to architecture. He was in practice with Thomas Vaughn from 1861 until his untimely death in 1869; then he was joined in partnership with Harold Ainsworth Peto (1854-1933) until he retired in 1892 to pursue his gardening and collecting interests and finally he was joined by a much younger man Alfred Bowman Yeates (1867-1944). This lasted until George retired at the age of 82 in 1921. Hilary Grainger makes the point that this was a very deliberate choice to continue in partnership after Peto’s departure, he liked the support of a partner in what was a large practice with many pupils and it enabled him to continue travelling on the continent sketching architecture. The patterns of patronage are skilfully explored. His association with Peto, a younger son of the great Victorian contractor and railway builder, Sir Samuel Morton Peto, was certainly an invaluable introduction into the world of building contracting leading specifically to notable work in Collingham and Harrington Gardens and probably the commission for Batsford in Gloucestershire. Harold Peto led the life of an aesthete, devoted to the pursuit of beauty but was invaluable in dealing with clients while George got on with the practicalities of architecture. The great London estates of the aristocratic Grosvenor and Cadogan families and the fields of Kensington were being developed with new commercial premises and domestic housing; successful entrepreneurs were demanding great country houses. Darcy Bradell, who joined the office in 1902, recalled meeting Charles Gould, the office manager who told him of the ‘eighties and ‘nineties’ when Harold Peto was present, they were the ‘golden years’, when the firm was building ‘half’ South Kensington.

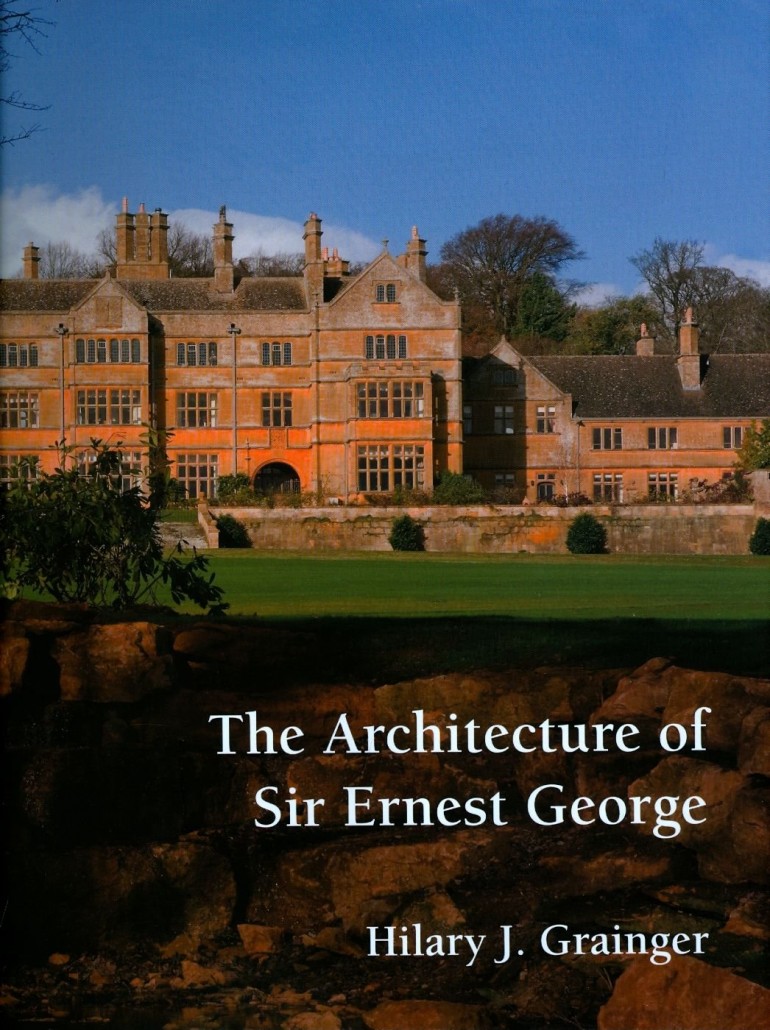

Rousdon (1874-83) in Devon, which was built for Sir Henry William Peek of Peek Frean & Co of biscuit making fame, launched George’s country house practice in a grand way. Not only was he responsible for the main house, but also a church and the associated estate buildings. The main house has been described as Franco-Flemish and late Tudor with masses of picturesque detail, recalling sketches done in Germany and Switzerland. In London by the 1870s the ‘Queen Anne’ style had emerged as a favoured style with clients. Ernest George began fairly soberly but went on to add detailing with a strong Flemish flavour which is found in the town houses he did in Collingham and Harrington Gardens (1881-4) and Cadogan Square, Chelsea (1886). Reminiscent of the great burghers’ houses of Antwerp, they were built on a monumental scale and show George’s skill at internal planning.

They were known to Lutyens who in later years distanced himself from George of whom he said disparagingly that he was ‘an architect who took each year three weeks holiday abroad and returned with overflowing sketchbooks. When called on for a project he would look through these and choose some picturesque turret or gable from Holland, France or Spain and round it weave his design.’ Another house that Lutyens must have known was Batsford Park in Gloucestershire (1888-1893) done for Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford. His fellow pupil in the office, Guy Dawber was the clerk of works on site. Fourteen years on from starting at Rousdon the more austere design reflected the severity of Cotswold architecture. George believed in the gentle persuasion of his clients, counselling his colleagues at the RIBA in 1893 that the clients ‘should have the most careful consideration even when at first they seem opposed to our views of what is best’. At Batsford Freeman-Mitford was given a very fine house, beautifully built by Peto Bros, well planned with a series of reception rooms arranged enfilade where he could fulfil his role as a landed gentleman and a political host.

Other commissions included buildings for the Temperance Movement, the crematorium at Golders Green and the Royal Academy of Music (1910-11); sometimes details of costs are available and are evidence of a highly successful practice. The appendix on ‘The Office’ includes the recollections of office life of several pupils and a chart indicating when the 79 pupil architects passed through the ‘Eton of architects’ offices. There is also a comprehensive catalogue of works, invaluable to those who are seriously interested. Reluctant to admit it, Lutyens must have learnt a great deal in his brief time with Ernest George and established professional friendships. When Ernest George died in 1922, he had received many public honours and his funeral at Golders Green Crematorium was attended by many who had worked with him. His estate amounted to over £32,000, considerable wealth in those days, evidence of a life well spent.

Hilary Grainger who gave a Study Day at Goddards in June 2010 on Ernest George is to be congratulated on this book. Copies of ‘The Architecture of Sir Ernest George’ are available from Amazon and The Lutyens Trust hopes to visit houses in Collingham and Harrington Gardens in 2012.

Janet Allen