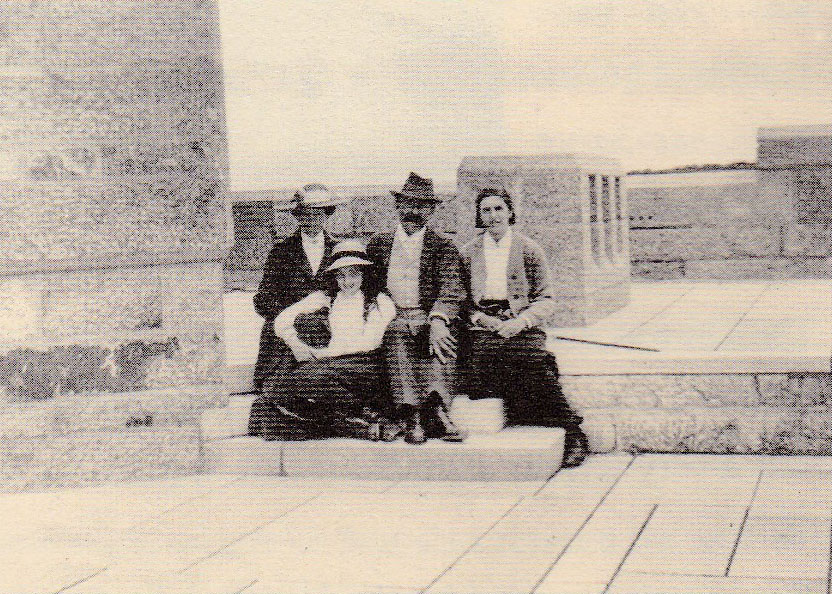

Drewe family on the roof – a granite world. (Photo Drewe family album c.1920)

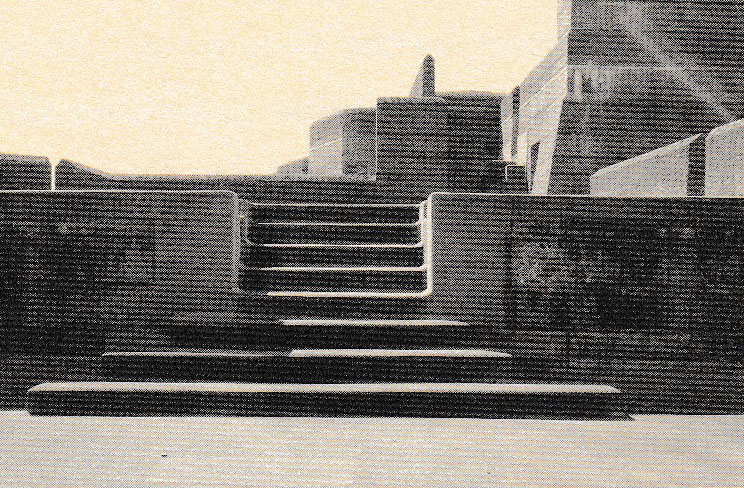

Granite paving removed and the architectural coherence of the flat roof lost under a sea of asphalt laid in the 1960s.

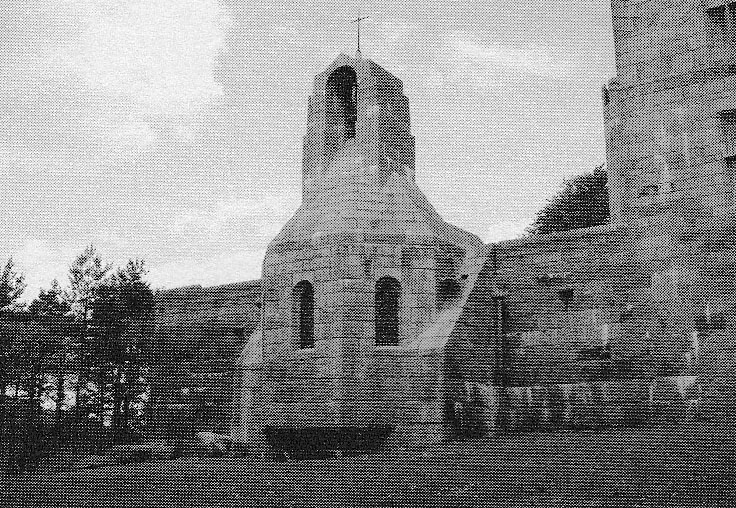

‘Free Lime’ precipitate arising from water build up in the chapel elevations. Lead flashings introduced in the 1980s.

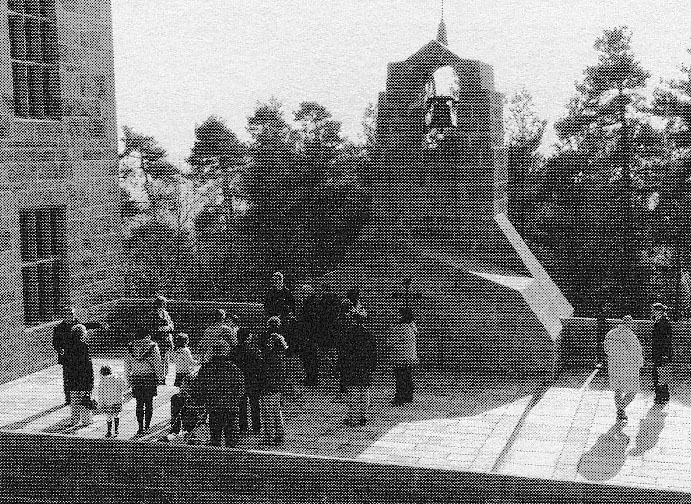

‘Visitors enjoying the restored chapel roof.’

Photograph by C. Goddard

Remedial Work at Castle Drogo

by Peter Inskip

Lutyens always believed that ‘a building of one material is for some reason much more noble than one of many. It may be the accent it gives of sincerity. The persistence of texture and definite unity.’ Castle Drogo, a commission of 1910, appears as a granite house par excellence and rises as an almost natural outcrop on Dartmoor. Not only is it granite outside, but one is aware off the material throughout the interior; even when progressively softened by overlays of panelling and plaster, depending on the status and use of a room, Lutyens’s detailing always ensures that the underlying granite is omnipresent.

The flat roofs were no exception, and a carefully considered grid of granite paving extended between the granite parapets and roof structures. The variation of the height of the principal bedrooms on the floor below generated roof terraces at varying levels, and these were treated almost as a promenade architecturale that extended across the whole house, connected by flights of steps and dramatic, tortuous castle-like passages. Between the Wars, the family enjoyed the magical Drogo roofscape and Basil Drewe, the son of Lutyens’s client, remembered that ‘it was marvellous as you could be out there in the altogether’ – a concept that we generally associate more with the heroic modern movement.

Throughout its life, Drogo has had problems with its construction. All the chimneys smoked – except for the one in the Library, if the front door was left ajar. However, Basil Drewe said that they never told Lutyens as he was such a nice person and they did not want to worry him; he felt it did not matter as long as the library fire worked and they had free electricity from the River Teign to heat the rest of the house.

The roof, however, was more of a problem. Below the granite paving, Lutyens had used asphalt to provide the waterproof membrane. It was a comparatively new material, brought from pits in the Caribbean, and one which he was to use extensively on his great commercial buildings in the City. However, knowledge of the behaviour of building materials and the movement of moisture in buildings was very limited at the time. The roof was found to leak and the Drewes were carrying out repairs well before the Second War. The causes of failure, however, were not addressed and the new asphalt was treated generally as patch repairs laid over the old. In the early years, the repairs involved temporarily lifting the granite slabs to search for the areas of failure, but by the 1960s, virtually all of the granite paving had been stripped away to facilitate re-asphalting.

The Drewes always said that the slabs were in store, but they have never come to light and only those for the chapel and kitchen court survive. The loss of the paving was a very serious alteration to the appearance of the castle.

Drogo was acquired by the National Trust in 1974. Between 1983 and 1989 the parapets around the whole of the roof were dismantled to enable a lead damp proof course to be introduced and new asphalt was laid across all of the roof planes. Although this appeared to be successful, signs of failure began to appear in the next ten years. In the light of this, the Trust decided to carry out holding repairs and commission a comprehensive investigation. Working closely with the Trust and English Heritage, the appointed architects, Peter Inskip, Stephen Gee and Mehmet Berker, recommended that any solutions should be based on a long-term investigation programme into the causes of the problems, since this approach was more conducive to reaching strategic solutions than a report summarising the castle’s condition. On-site testing started in 1996.

As the complete understanding of the heritage asset is essential to any project involving the repair of an historic building, the Lutyens drawings and papers at Drogo, as well as those in the Collection of the British Architectural Library and in private collections were consulted; during the research a further tranche of preliminary designs surfaced in Australia. The information was analysed against the built fabric. Not only did this reveal the technical detailing, but it also confirmed the architect’s aesthetic vision.

In his drawings of November 1911, Lutyens had shown the principal walls as six feet thick to provide a true castle effect. However, Julius Drewe rejected the proposal as the walls were of cavity construction and real castles had solid walls. The walls, therefore, were constructed with a solid rubble core. To ensure that water did not travel through them, Lutyens incorporated vertical asphalt tanking to protect the inner leaf and the continuity of this with the horizontal membranes that protected the various roof planes was an essential part of the detailing. The design of the roof was, therefore, integral to that of the walls. Since there was no opportunity for differential movement, it is likely that the asphalt cracked and the building began to leak as soon as it was finished.

It was found that the subsequent campaigns of repairs had also severed the asphalt at the vertical abutments. This resulted in water being entrained beneath the new asphalt instead of being drained from the building. The severe water penetration into the chapel was the direct result of the loss of the relationship of its roofing with the tanking of the adjacent west elevation of the south wing that towered fifty feet above it. In addition, heavy precipitates of calcium carbonate started to dramatically leach out of the mortar joints following the repointing of the elevations at the same time. With the introduction of lead flashings in a further attempt to solve the problems, the essential simplicity of the elevations that developed in parallel with Lutyens’s work at New Delhi and Thiepval was seriously compromised by the late 20th century.

In most cases, a return to the original construction methods is the ideal repair methodology for historic buildings. However, this was clearly not appropriate at Drogo as the problems resulted from the original choice of materials which was flawed and it was impossible to gain access to replace the critical asphalt junctions without dismantling considerable amounts of historic masonry. A new approach, therefore, had to be determined and this had to not only resolve the technical issues, but recover the quality of the elevations that had been eroded by the modifications.

A series of tests were carried out over a two-year period on the west elevation of the south wing to ascertain the extent of the water penetration and to test the efficacy of existing and new types of mortar. Non-destructive techniques were used to study the arrangement and condition of materials within the masonry structures. Both thermography and pulsed radar were used to locate differences in moisture content across the complete building envelope, and probes set in the mortar joints measured how much water penetration was occurring through the elevations. The resulting data was downloaded regularly to a computer which was coupled to a weather station set up on the roof so that water penetration could be analysed against meteorological conditions on the exposed site.

For the stonework, Lutyens used early cement based mortars with considerable similarities to hydraulic lime mortars. However, he used granite aggregate and, because of this, his mortars have proved to be unstable with little resistance to water ingress. These had been replaced in the 1980s with a Portland cement mortar with a waterproofing additive; it failed due to shrinkage relatively quickly. The new cement mortars were found to have led to a water build-up within the masonry and hindered the evaporation of moisture out through the jointing. The ‘Free lime’ precipitate that had so disfigured the elevations was a direct result of water escaping when it did find a route. Through an iterative process of on-site trials over six years, an Italian hydraulic lime mortar was identified as a suitable replacement.

With the roofing, it could be seen that the original build-up was technically deficient and the subsequent repair solutions over the years were largely ineffective. Lutyens’s roofscape could be considered as very ‘modern’, but the problems of a ‘cold roof’ were not known at the time and it was designed without insulation or ventilation and with no provision for accommodating thermal movement at abutments with concrete, steel and granite. It was, therefore, decided to employ modern roofing technology and a strategy was developed with Bauder, a German firm of roofing specialists, for the design of the waterproofing membrane, insulation and ballast to ensure performance and longevity of the construction and to minimise maintenance requirements. This was used in conjunction with Ruberoid cloaks and damp proof courses. It will provide an inverted ‘warm’ roof deck that will eliminate the interstitial as well as the surface condensation that affected so many of the bedrooms. The choice of the membrane was determined by its resistance to differential movement, that of the insulation above the membrane by its ability to resist interstitial condensation damage and cold bridging problems. Reinstatement of granite slabs matching the original design will prevent wind uplift of the insulation.

The chapel has now been repaired as the first phase of a building programme that will address the whole castle. However, before any further phase is carried out the completed work is being monitored for a period of two years. What is good is that the strategy for the technical repair has also meant the recovery of Lutyens’s design intentions. The removal of the extraneous flashings, the cleaning off of the precipitate, the re-pointing of the walls and the reinstatement of the granite paving have transformed Drogo and recovered elements of the design whose quality had been eroded considerably over the years. When complete, it will not only have secured the building, but have recovered the quality of a great work of art.

Peter Inskip