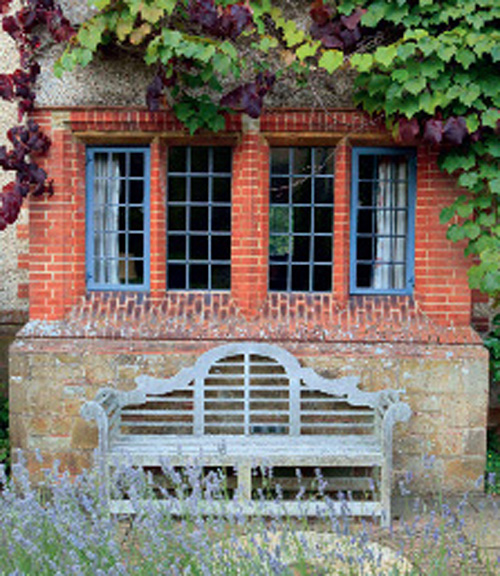

Goddards inside and out — from bowling alley to a charming detail of windows and Lutyens bench, courtesy of the Landmark Trust

New Book: Landmark – A History of Britain in 50 Buildings

Reviewed by Jane Ridley

The Landmark Trust is 50 this year. It is surely one of the great British success stories of the last half-century. Forty years ago, when my mother Clayre Percy started to work for it, no one could have predicted how it would develop. Clayre used to set off on mysterious expeditions with Christian Smith or Sonia Rolt in a car packed with what to my uneducated eye seemed like eccentric junk. Her bookshelves bulged with topographical books. She spent wet afternoons inking in public footpaths with a pen on large-scale maps and researching histories of houses. The early Landmark workers were a small band of pioneers and enthusiasts. As this magnificent book by the Trust’s director, Anna Keay, and historian Caroline Stanford shows (Frances Lincoln, £25), their achievement was astonishing.

The Trust was the brainchild of John Smith (Christian’s husband), a man of remarkable originality who was clever with money and passionate about idiosyncratic buildings. using funds from his Manifold Trust, he bought small, historic houses and restored them employing the best traditional craftsmanship. “Do you detect a terrible whiff of privilege about all this?” asks Griff Rhys Jones in his foreword to the book. “Well, don’t.” The houses are available to anyone to rent; to do so, all you need is a computer or phone.

Keay has picked 50 of the Landmark’s 196 buildings, starting with medieval Purton Green, and used them to tell the story of English history. The names roll off the tongue — Lundy Castle, St Winifred’s Well, Rosslyn Castle, Martello Tower, The Pineapple… Her crisp text is illustrated with sumptuous photographs to make a strikingly handsome book.

One of the stars is Lutyens’s Goddards. This was generously left to The Lutyens Trust by the Hall family, and in 1996 the Landmark took a long lease and restored it. Goddards was built by Lutyens from 1898 to 1900 for Frederick Mirrielees as a “home of rest” for “ladies of small means”. In 1910, he adapted and extended it as a private house. Now the people who stay there can once more enjoy the “simplicity, beauty and sense of escape that were part of the original enterprise of Lutyens and Mirrielees”.

Country Life

Country Life