Winkworth Farm, Hascombe

‘Shootlands’ Abinger Common

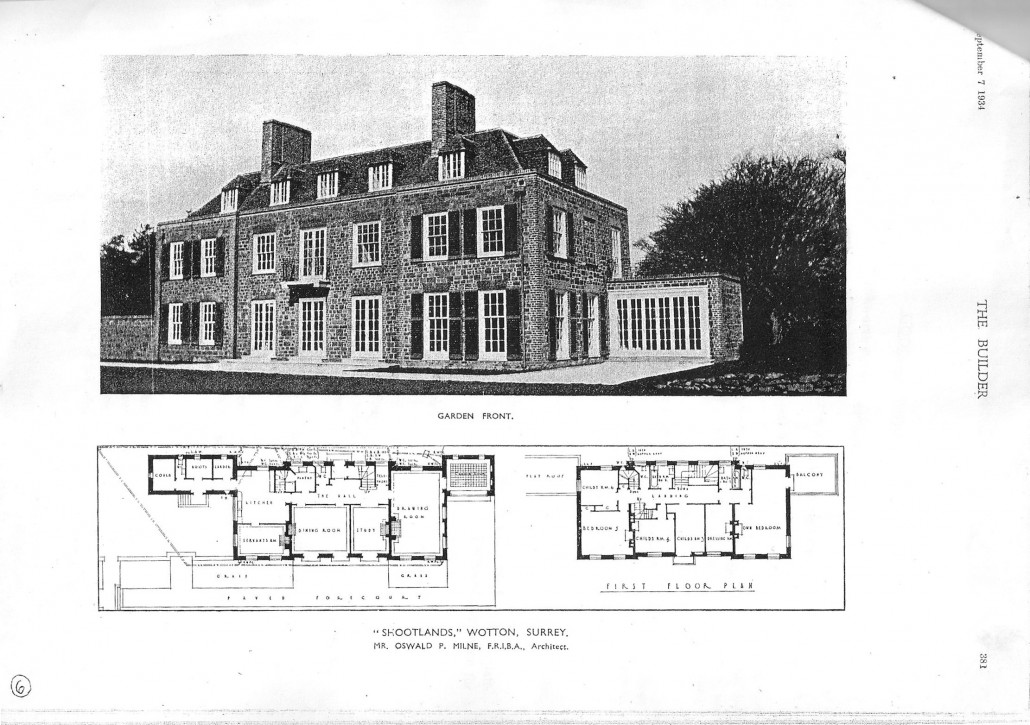

‘Shootlands’ Builder’s Scan

Goddards Study Day 2012

Visit to Winkworth Farm in Hascombe and

Shootlands in Abinger Common

Wednesday, 13 June 2012

Never one given to dishing out high praise too liberally, the architectural chronicler Nikolaus Pevsner must have been especially smitten when he came across Winkworth Farm and its “unbelievably picturesque quad”. Yet the charms of this quirky, timber-framed house in the heart of the Surrey hills extend well beyond its good looks to other claims to fame. The house’s lived-in face, with its gingerbread appeal, owes much to its age, as it was built between 1580 and 1600 for a local yeoman farmer at Hascombe, south of Godalming. It was hardly the height of fashion in its day, as timber framed, Elizabethan construction was on its way out, making way for newfangled Dutch brick buildings. But the property also owes some of its charm to Sir Edwin Lutyens, who, in 1895, remodelled the mid-18th century barn on the right of the property, joining it to the house, and lengthening it to make a hallway. His hand can be seen in the corner windows, which were favored by him, in tiles set end-on into walls, and in some Bargate stone window surrounds. His closest pupil, J D Coleridge, designed a rear extension in 1908. Gertrude Jekyll planted part of Winkworth’s garden, and a garden wall and terrace are attributed to her. She had

taken up photography in the 1880s, and took before-and-after photographs of Lutyens’s work at Winkworth. The architect F W Troup altered her garden in 1914, adding spiral steps, while making some changes to the house’s interior. In 1918, the house was bought by Dr Wilfred Fox, a leading dermatologist, based at St George’s Hospital, who, during his 40 years at Winkworth, acquired the adjoining Thorncombe Estate. In 1938, he began planting an arboretum in the then wild Thorncombe Valley, near the house. He packed it with 1,000 species of shrubs and trees that give impressive spring displays and blazing autumn shows, which are reflected in two lakes at the valley bottom. In 1952, he gave the arboretum to the National Trust, and it is still open to the public. When, in 1962, the wildlife artist and campaigner David Shepherd bought the farmhouse from the late Dr Fox’s estate, he said it was covered in “cheap panelling”. Even so, he lived there for 39 years, moulding it to his taste. He kept a gipsy caravan in the garden, and, next door to the kitchen, created an early-Victorian shop front with a bow window and a wooden, panelled door with a bell that tings when a “customer” enters. Over this is a sign, “Winkworth and Daughters 1963”, a reference to his four daughters. It even has an old-fashioned delivery bike, with a basket. Shepherd later bought an old oak barn that had stood at Parkhurst Farm, Sussex, until it was blown down in the great 1987 storm, and re-erected it to use as his studio. He joined it to the house by an “underground tunnel” – he had a deep trench dug, walled and roofed. That tunnel, which is accessed from the cellar, was his “commute” to work, where he produced his famous paintings of steam trains, elephants and other African wildlife. Now

owned by a young family and obviously loved, the house and garden has been restored to an immaculate level.

Then next it was on to Shootlands, a sophisticated essay in the restrained neo-Georgian of 1934. The son of an architect who had been a pupil of Sir Arthur Blomfield, Oswald Partridge Milne was also articled to Sir Arthur William Blomfield from 1898 to 1901, and remained as his assistant until 1902 when he joined the office of Edwin Landseer Lutyens as his assistant. He left in 1904 to commence practice on his own account in London. His other work included some of the main interiors of Claridge’s Hotel in London and many country houses. Other

houses by him open to the public are Coleton Fishacre in South Devon and Nuffield Place near Henley-on-Thames. If John Entwistle can write of the sense of peacock feathers and aesthetic influence evident in our visit to Harrington Gardens, certainly here one could feel the evident sophistication of the thirties, possibly as shown in Noel Coward’s Brief Encounter. Seemingly a very simply designed house, almost severe when first built, the house has a carefully delineated plan that broke the space down into pleasant living areas of different sizes for either entertaining or remaining in a small family group. Built with a third of the ground floor originally given over to service areas, the current owners opened that section out into a large kitchen with a new conservatory, thus the ground floor is now a sequence of carefully shaped living spaces, all on a generous but never forbidding scale. In fact the more one looks, the more one notices the careful detail – the panelled walls of the study or the sophisticated fireplace surrounds in the drawing and dining rooms. You can see that Milne not only had a taste for a combination of elements from both old and new schools of design, but also always had an emphasis on comfort. While the symmetrical entrance front would drive modernists crazy with its staircase hidden behind blind casement windows, the house has a very modern sense of opening to the garden. Every principal living room has direct garden access to the exterior and every room has large windows opening to the garden around the house. While the physical material of the house looks back to the Arts & Crafts Movement – roughly hewn yellow local stone – the form is sophisticated neo-Georgian and yet the whole design is refreshingly modern: a reminder of that sophisticated inter-war world.

Paul Waite