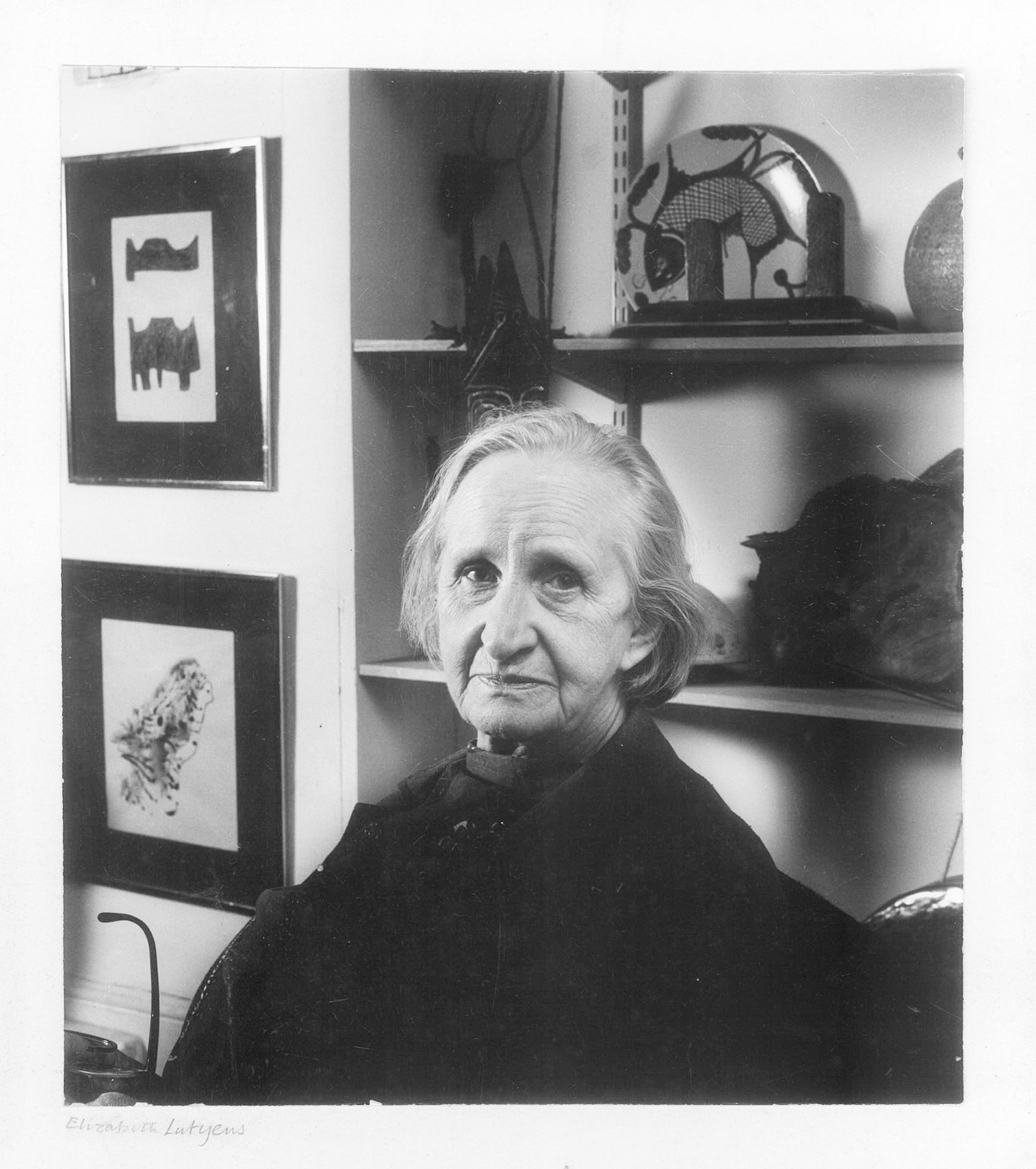

Elisabeth Lutyens, courtesy of Conrad Clark

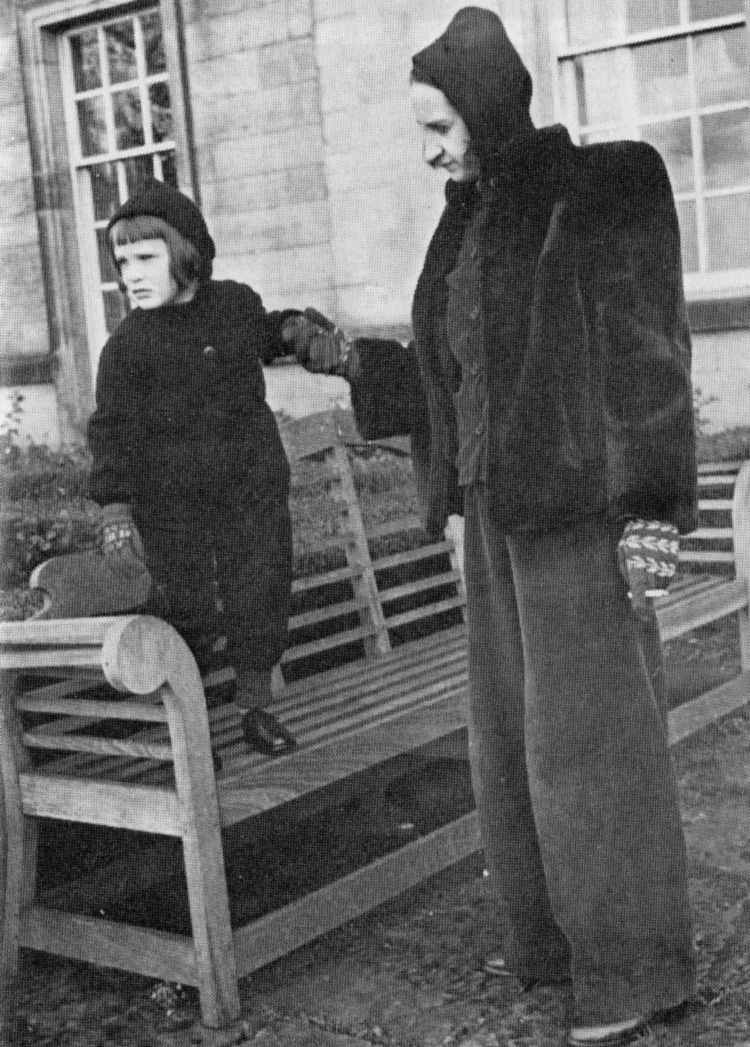

Elisabeth and Rose — on a Lutyens bench — at the Ridleys’ home, Blagdon Hall, whose gardens were remodelled by Lutyens

Composer Elisabeth Lutyens, daughter of Edwin

Remembered by Rose Abdalla, Tess Fetherston, Conrad Clark, Jane Ridley and Robert Saxton

Last March, BBC4 aired its programme In Their Own Words: 20th-Century Composers, which collected rare footage of such composers as Igor Stravinsky, Aaron Copland and Elisabeth Lutyens. The programme was a reminder of the respect in which Elisabeth — one of Edwin and Emily’s five children, who was born in London in 1906 — is held today, despite the challenging nature of her avant-garde music. Elisabeth was highly regarded by her peers, not least by Stravinsky, with whom she became friends. A photo in the 1986 biography of her, A Pilgrim Soul, shows them together. With her characteristic, rather barbed wit, Elisabeth described him — on seeing a photo of him before they met — as having ‘a face like a very piercing dachshund with glasses… and a squint’.

The BBC programme inspired us to take a fresh look at her career, life and colourful, unconventional personality. We’re fortunate to have been able to talk to three of her children — Rose and Tess who live in London and Conrad who is based in Melbourne. They were kind enough to relay their unique, personal recollections of their mother, who was often known as Liz or Betty. And we spoke to one of her former pupils Robert Saxton, now Fellow and Tutor in Music at Worcester College, Oxford University, who remembers her fondly. ‘Liz was my teacher for four years — most lessons lasting at least five hours! — then we remained friends,’ he says. ‘I proofread for her and she, my parents and then my wife, Teresa, all got on very well. she is often thought of, and admired, as the first 20-Century British composer to use serial technique. Thirty years after her death, a clearer perspective reveals that she employed the principles of 12-note composition at the service of a highly individual vision, technique being invariably the servant of her often burning inspiration.’

Elisabeth set her sights on becoming a composer, aged nine. In 1922, she studied at the École Normale de Musique de Paris, finding 1920s Paris exciting and inspiring, then at the Royal College of Music in London under Harold Darke. While still at college, she had a setting of Keats’s poem To Sleep performed. Elisabeth disapproved of the ‘overblown sound’ of Gustav Mahler and similar composers, preferring to work with sparse textures. she was also fond of Claude Debussy. she first used a 12-note series (originally invented by Arnold Schoenberg) in Chamber Concert No 1 (1939). But she didn’t always limit herself to it and sometimes used a self-created, 14-note technique.

Elisabeth juggled her career with two marriages and motherhood. In 1933, she married Ian Glennie, and they had a son, Sebastian, and twins Rose and Tess. The marriage wasn’t happy and in 1938 Elisabeth left Glennie for Edward Clark, a conductor and former BBC producer who had studied with Schoenberg. She and Clark had another child, Conrad, in 1941, but didn’t marry until the following year. Clark had left the BBC under a cloud and was unemployed until his death in 1962, so Elisabeth was the family breadwinner. She paid their bills by composing film scores for Hammer horror movies, including The Skull (1965) and Theatre of Death (1966), as well as music for documentary films and BBC radio and TV programmes. she was prolific and known in the business for her quip, ‘Do you want it good, or do you want it Wednesday?’ she also tutored many young composers.

But work didn’t rule her life: she and Clark frequently threw parties at their flat. Elisabeth was gregarious, liked a drink, smoked heavily and cut a flamboyant figure — she usually painted her nails red or green.

At first, her avant-garde compositions weren’t well received — her chamber opera Infidelio of 1954 and cantata De Amore of 1957 weren’t performed until 1973. But she later became accepted as a leading British composer, known for pieces such as O Saisons, O Chateaux (1946), the chamber opera The Pit (1947), Concertante (1950), Quincunx (1959), The Country of Stars (1963), Vision of Youth (1970) and Echoi (1979).

In 1972, she published her autobiography A Goldfish Bowl. Right up until her death in 1983, she remained a forceful, fiery character.

Elisabeth remembered by her daughter Rose Abdalla

‘My mother had a large appetite for life. My sister and I miss her a lot, we think about her a lot. When she was studying in Paris, she had a wide circle of friends. She was very sociable. She felt very close to the old and to the very young, especially babies. She went bonkers over babies. She was also very affectionate towards and supportive of her pupils. She used to send one of them to buy her underwear, because she hated shopping when she was older.

‘When I was an adult, we all lived in the same house for 14 years on King Henry’s Road, Chalk Farm, London — we on the ground floor, my mother on the top floor. We’d all go out together a lot. My husband, Mohammed, a potter, had his studio there too. My Sudanese mother-in-law, who didn’t speak a word of English, spent a lot of time with Liz. But they got on like a house on fire. They’d often watch Rock Hudson films together.

‘Her second husband, Edward, was the love of her life. She would write notes to him saying “Love Lizzy more”, and he would respond by writing notes in French. I remember she always said she’d come back in another life as Rameses!’

By her daughter Tess Fetherston

‘My mother was by far the most interesting woman I ever knew. She was a unique individual cursed with a difficult and discontented temperament but blessed with an acerbic wit and a great sense of fun. Friends would beat a path to her door for the stimulating talk they knew they would find there. She would call friends to invite them over and if they were otherwise engaged they were peremptorily summoned. When they got to her house, she’d be there on the telephone with a glass of wine and a cigarette to hand. There was always a lot of good gossip and good wine round at hers. The gin and tonic didn’t come with real lemon but with juice squeezed out of a Jif plastic lemon because she said lemons always went off quickly.’

And by son her Conrad Clark

‘Some people might have called my mother eccentric but she was just a very strong individual who forged her character through many struggles in her life. She was also very funny, sometimes scandalously so, but also incredibly warm and generous. Her extreme sensitivity made her defensive which came out in her humour and a sometimes forbidding visage, and which gave her a reputation for being tough.

‘She was totally uncompromising when it came to her music and I think this gave it its originality. In spite of being known by the label or epithet “intellectual”, she was profoundly emotional. The range of her work also is amazing as is her range of instrumentation and the sound world she created. Her love of poetry was a source of many lyrical pieces as well as a very strong sense of drama. some of her most beautiful music was written for the theatre, in particular her collaborations with director Minos Volanakis on new productions of ancient Greek plays such as euripides’s The Bacchae. Her Hammer Horror scores became legendary. she almost hero-worshipped her father Ned and felt she was the only one — being creative herself — who truly understood him. Alas, I don’t remember knowing Edwin myself, but apparently I used to shuffle his patience cards although he never minded!’

Conrad recently showed his sculptures based on music and landscape — Miles Davis in the Oz Desert and Down at the Crossroads — at an exhibition at the Association of Sculptors of Victoria. He is also hoping to set up a stone-carving studio in India in the near future.

For more information, visit www.conradclark.com.au, which features a YouTube interview with him, plus information on Elisabeth and Edwin Lutyens.

And by her great-niece Jane Ridley

‘Aunt Betty had very straight, short grey hair, a long, thin nose and thin, expressive hands. Her fingernails were painted red and she always wore trousers. she loved to make outrageous remarks, and her talk was peppered with “F***”s, which in the 1970s was cool — the more so when the f***ing and blinding came out of the brightly lipsticked mouth of one’s great-aunt. Great-aunts in the 70s were supposed to wear blouses and pearls and powder their noses, and Aunt Betty did none of the above, though she did pronounce “off” in the old-fashioned way with a long ‘o’, as in “B***** orf”.

‘Betty’s musical genes bypassed my philistine genome, so her difficult, modern music was closed to me. But I loved to visit her in her flat and listen to her talk, always fuelled with a generous bottle of champagne which she could ill afford. Her life story was of one of battles — rebelling against her parents, sparring with her siblings, struggling for recognition in the male-dominated music business; or warring against the middle classes (she had time only for the working classes and the aristocracy) and, of course, challenging authority in any shape or form. As her biographers Meirion and Susie Harries perceptively observed, fighting was for her an art form, and it energised and sustained her. Some people thought her colourful persona — the green suede boots, butterfly glasses and white Persian fur coat — was invented to shock. To me in my 20s, it just seemed that she hadn’t got old. She possessed a timeless ability to connect and, like her sisters, she was wickedly, deliciously direct.’