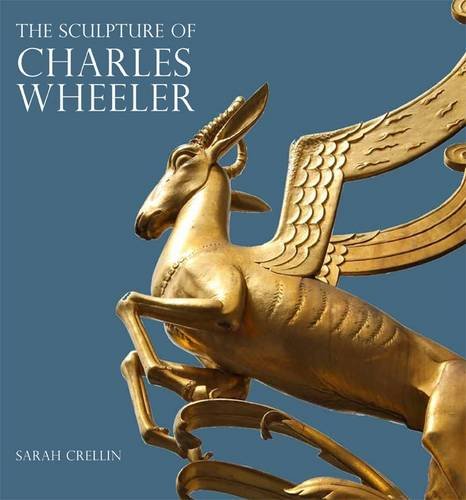

Book Review – The Sculpture of Charles Wheeler: Sarah Crellin

Lund Humphries, (with the Henry Moore Foundation) £60.00 200 pages 245×295

This beautifully produced book is within the British Sculptors and Sculpture series, designed to widen the understanding of sculpture in twentieth-century Britain, where Sarah Crellin’s research interests are centred. The first half of the book is a scholarly review of the life of Sir Charles Wheeler PRA (1892 – 1974), his work, and place in the history of British sculpture. The second is the first ever catalogue of his work, with most entries illustrated by photographs. These, like those supporting the narrative, are in black and white.

The central part of the text describes Wheeler’s architectural sculpture in the twenty years between the wars. These were, as Crellin points out, ‘the most productive and enjoyable of his career, when his alliance with Herbert Baker provided the financial and professional security that enabled him to pursue his art full-time and take major roles in art institutions’.

Wheeler’s studies at the Royal College of Art embraced William Morris’s and John Ruskin’s concept of architecture as the ‘master art’ in which all the crafts were unified. This came alive for Wheeler when he was taken up by Herbert Baker, after an introduction by Douglas St. Leger, Baker’s young assistant.

Wheeler completed his course as the Great War came to an end. With very slender means he embarked on his career and after two years with little work was on the point of giving up his studio when Baker introduced him to Rudyard Kipling who wanted a memorial plaque to his son John, killed at Loos in 1915. From then on Wheeler worked with Baker on most of the latter’s important buildings and on his two finest memorials, the Winchester College Memorial Cloister and the Indian Memorial to the Missing at Neuve Chapelle. It was at the former that St. Leger encouraged Wheeler to carve direct for the first time, offering to replace the block of stone if anything went wrong. All of this work is described in engrossing detail.

There is much, rightly, about the personal as well as the professional relationship that developed between Wheeler and Baker. The book contains a fascinating description of their partnership from the sculptor’s perspective. In spite of the age gap of thirty years they shared so many interests and beliefs that there developed what Crellin describes as ‘a paternal and filial bond’. They met frequently, often for an early morning walk before breakfast at Baker’s house, and they travelled to Italy and Greece to study European art. The author writes with sensitivity about the relationship and the way they worked together. She touches on the difficulties experienced by Baker after the Great War, which emanated from Lutyens’s anger and distress over the gradient in New Delhi, exacerbated by Baker’s appointment at the Bank of England, but she is not as blunt as Wheeler in his autobiography, where he said ‘the quarrel caused Baker much pain and he very often referred to it in considerable sadness. He was far more generous to Lutyens than he to him’.

Architectural patronage was the key to Wheeler’s success and was far from being exclusively from Baker. There were collaborations with Charles Holden, Edward Maufe, Oliver Hill, and with Sir Edwin Lutyens who had an important influence on his career. Crellin says ‘Lutyens was associated with the project that finally released Wheeler’s sculpture from buildings and placed it in the middle of London’s most famous public space, Trafalgar Square’. This was the creation of national memorials to Admirals Lord Jellicoe and Lord Beatty. The installation was thwarted by the Second World War and not unveiled until four years after Lutyens died. This is a book, well researched and written, which will inform and delight all those who are interested in the story of architectural sculpture between the wars.

James Offen