Book Review

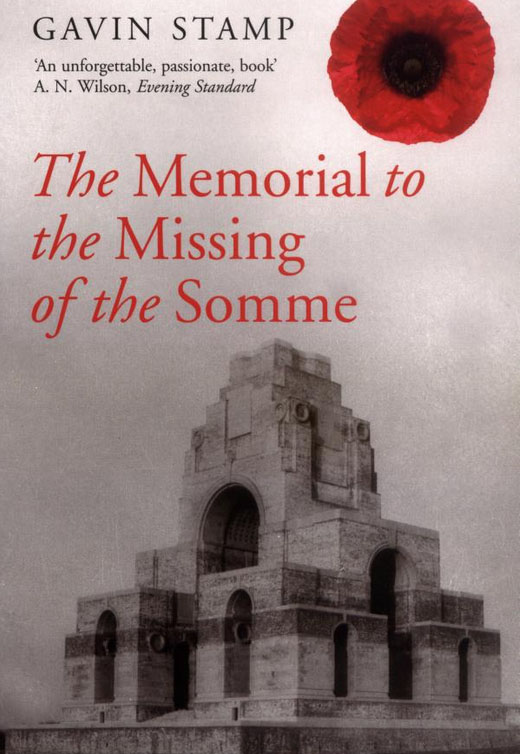

The Memorial to the Missing of the Somme by Gavin Stamp

This month [July] saw the 90th anniversary of the First Battle of the Somme. In a corner of Northern France, near the small village of Thiepval, wave upon wave of young British soldiers hurled themselves over the top of their trenches only to be mown down by German machine guns. July 1, 1916 was an unmitigated disaster. In one day almost 20,000 British soldiers were killed, the greatest loss of life in British military history, and they failed to break the German line.

The Germans had constructed dug-outs reinforced with concrete which made their line impregnable. Before attacking, the British bombarded the Germans for seven days, but the shells made little impact. So when the British advanced, wearing cloth uniforms with no body armour, mass slaughter was inevitable. Rather than admit defeat and order a tactical withdrawal, Field-Marshal Haig, the British commander, stepped up the campaign. The Somme became a bloodbath of attrition. Not until November 1916 did the British and French break through the enemy lines, at a total cost of over a million casualties on both sides.

Gavin Stamp’s brilliant book recounts how the battle of the Somme came to be commemorated in the Memorial to the Missing at Thiepval. The Memorial was designed by Edwin Lutyens, architect to the Imperial War Graves Commission. The brainchild of Fabian Ware, the Commission undertook to provide proper cemeteries for the mangled bodies buried in makeshift graves beneath the battlefields.

Almost 1,000 British war cemeteries were built in Northern France, where the fallen were ordered with the same ruthlessness in death as they had been in battle. Exhumation of bodies was forbidden, no private memorials were allowed, all must be given the same plain white headstone whether officers or men.

The British are notorious for the dullness of their government architecture, but at Thiepval officials commissioned a monument of genius. Lutyens had begun his career designing Arts and Crafts villas in Surrey, but by the end of the First World War he had evolved a timeless ‘elemental’ classicism which chimed exactly with the sombre public mood. Thiepval is an extraordinarily complex structure of arches piled upon arches, all recessed to give the same sort of dynamic effect as Lutyens’s other great war memorial, the Cenotaph in Whitehall. Every available surface is carved with the names of the 73,357 missing. Gavin Stamp lucidly describes the fiendish geometry involved, but to the layman the point about the memorial was that it broke with convention by being neither Christian nor triumphalist.

When the Thiepval Memorial was unveiled in 1932, it was received with a deafening silence. By then reaction had set in, and no one wanted to hear any more about the war. The £8 million spent by the British Government on commemorating their dead in France seemed a waste of money – even though it was the equivalent of a mere two days of the Passchendaele bombardment. Recently, as Lutyens’s reputation has revived and the First World War receded into historical perspective, Thiepval has become a place of pilgrimage, and the Memorial to the Missing has at last gained the critical recognition it deserves.

This book is a gem. I found it utterly absorbing, and read it in a single sitting. Stamp is a lifelong admirer of Lutyens, and he knows more than anyone else about his work, but this book is more than architectural history. It is an eloquent, moving lament for the futile waste and industrialised killing of the First World War, and indeed of the 20th century – an elegy which resonates powerfully today.

Jane Ridley

N.B. This review originally appeared in the Sunday Telegraph.