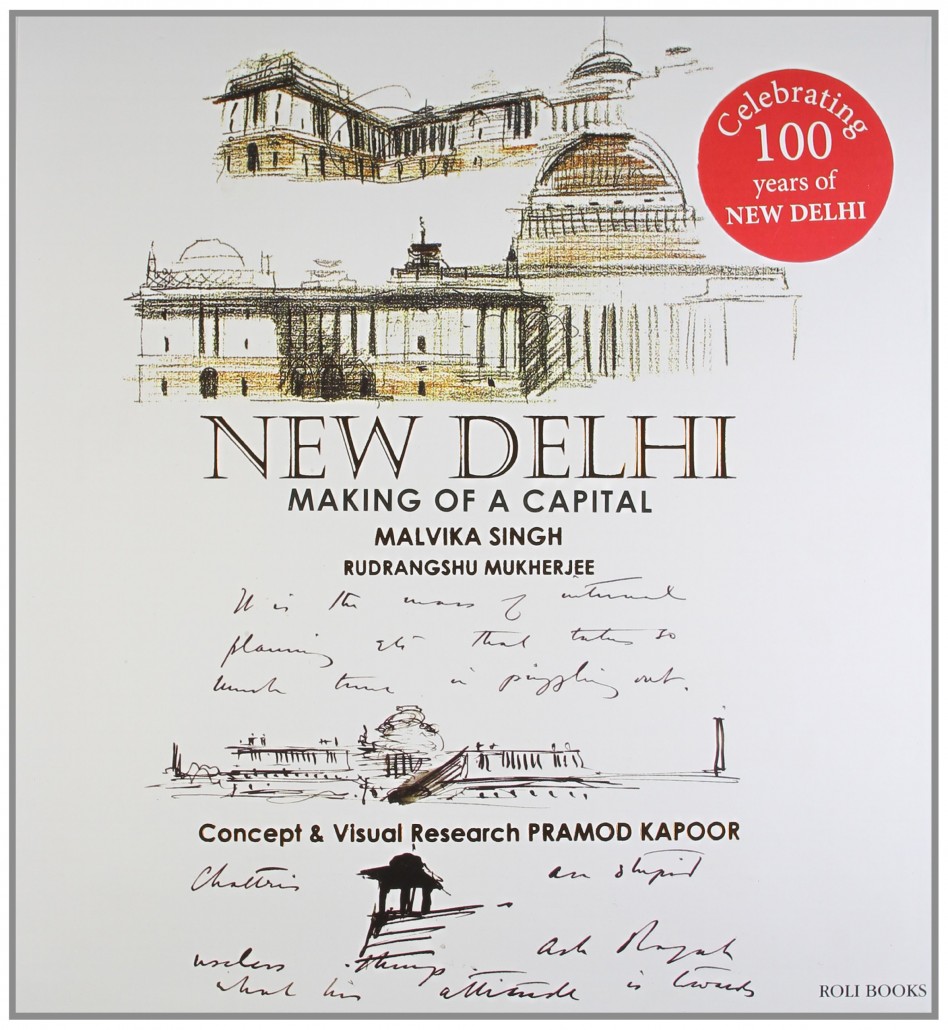

Book Review: New Delhi – Making of a Capital

Malvika Singh & Rudrangshu Mukherjee

Concept and Visual research Pramod Kapoor

2009, Lustre Press, Roli Books

This book is a fascinating compilation – a scrapbook perhaps – of photographs, facsimile newspaper articles, letters and drawings which record the actual construction of New Delhi. As such it is a valuable visual complement to Robert Grant Irving’s definitive Indian Summer, written in 1981.

But the aim of the book is a little different, focussing on the Indian participants in this great story – the unsung building contractors of the new city who had converged on Delhi from areas far away in what is now Pakistan. Conspicuous among the successful were Sujan Singh and his son Sobha Singh, who was later knighted for his contribution to the city. As a family they were already exceptional among builders when they came to Delhi in 1911. They owned land and a camel transport business in the Punjab and had helped construct the state’s railways. In New Delhi Sobha Singh acted as contractor for the South Secretarial Block, Viceroy’s Court and the Great Place, the War Memorial Arch, Baroda House and innumerable residences.

Sobha Singh was Malvika’s great-grandfather-in-law so it is understandable that she should take the lead in compiling this book and describing the evolution of the building of the city – covering the political situation, the Chief Architects, Lutyens and Baker, the question of style and the issue of the gradient.

But great credit should also go to Pramod Kapoor for his visual research in Britain, unearthing many images which have not been published before. Early photographs are especially daunting, taken from an observatory tower that was built in the centre of the construction site, showing multiple train lines for transporting materials crisscrossing the whole area. They give a true indication of the scale of the whole project. How important Hugh Keeling, Chief Engineer of Delhi, must have been in managing it all. Lutyens called him the ‘veritable mother’ of the city and of ‘all who worked for it’.

Also fascinating are the facsimile news cuttings chosen by Pramod from The Times, Daily Telegraph and Morning Post which show the extensive coverage given to the project in Britain. Several concern the problem of style. Baker’s article is well known but it is also good to read Lord Curzon’s which is much wiser. I had never seen one before – ‘The New Delhi: Sir E. Lutyens on Art in Building’ (The Times, 30 March 1921). One extract reads: ‘Englishmen will not sacrifice ground rent for a good building. Take a picture of Nash’s Regent Street and then see what they are making of the street today.’

Also included are several facsimile letters by Lutyens which show a concise and formal style which differs from his dashed-off way in writing to Lady Emily. One, written to The Morning Post on the 8th December 1923 about ‘Delhi’s Costly Glories’, refutes various myths about the new city including the statement that ‘up to now nearly £20,000,000 had been spent on New Delhi’; only £8,600,000 had been. It is also good to read in full two sad letters by Lutyens and Baker concluding the saga of the gradient, written in July 1922, after any attempt to correct the incline had finally been closed for good by the Government of India. Lutyens concluded ‘ we have to continue to work together and I am willing to do my best – but where trust and confidence has once been lost it can never be ‘glad confident morning again’.

There are many good things in this book but one of the best is the feeling expressed by Malvika in her foreword that many Indians today value the heritage of New Delhi and want to conserve it – for their own reasons.

Apparently the book has sold out in Delhi – to Dilli-wallahs.

Margaret Richardson