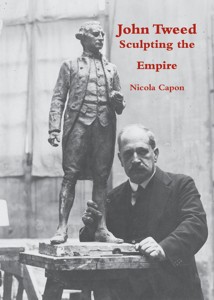

Book Review – John Tweed Sculpting the Empire by Nicola Capon

Spire Books in association with Reading Museum, 2013, ISBN 978-1-904965-43-5

John Tweed’s career coincided with the great imperial building schemes of the early 20th century, when in fact the idea of ‘empire’ was already in decline. Edwin Lutyens and John Tweed were both born in 1869 and it seems that their paths first crossed in 1890, when they were young men endeavouring to establish themselves in London. Jane Ridley tells us that Lutyens ‘belonged to a circle which had included Detmar Blow, Arthur Collie, a Bond Street dealer and a sculptor, John Tweed’.

This friendship continued into the 20th century and Lutyens was able to smooth John Tweed’s path in South Africa through his friendship with Herbert Baker, architect to Cecil Rhodes. Baker referred in his 1934 memoir of Rhodes to John Tweed, as ‘a young Scotch sculptor, since to become famous’. After his death in 1933 a memorial exhibition was held at the Imperial Institute opened by Princess Alice of Athlone, but since then he has become a shadowy figure. His daughters bequeathed his surviving works and archive to Reading Museum in 1963 and this publication is the result of research undertaken by Nicola Capon which illuminates a whole area of high artistic endeavour no longer familiar to us and gives members of the Lutyens Trust another insight into Edwin Lutyens as an artistic facilitator.

I doubt if there are many members of the Lutyens Trust who know the work of John Tweed; the sculptor associated with Lutyens’s great imperial enterprise in New Delhi is Charles Sargeant Jagger (1885-1934) whose Elephants in front of Rashtrapati Bhavan and statue of George V now banished to Coronation Park are familiar to us all. But, John Tweed’s work is worth reappraisal and by the standards of his day he was very successful, though he never became an Associate of the Royal Academy and was dismissed by those who championed modernity. The son of a Glasgow publisher, his early training was at the Glasgow School of Art before he moved south to London and worked in Hamo Thorneycroft’s studio. Paris beckoned and there he met the great Rodin. His father died when he was young and he was burdened with family responsibilities; like most artists his career path was constrained by the need to earn money besides developing his artistic sensibilities. Portraiture, monumental and memorial sculpture were the mainstays of many young sculptors though he always worked on his more personal ‘ideal’ figures. Nicola Capon’s research of John Tweed is not only a study of his work but also of the intricate patterns of patronage where friendships with society figures developed during portrait sittings often led to commissions for public monuments, many of which are found in far flung places, as in Tweed’s case, Aden, Australia and India.

Nicola Capon takes us through Edwin Lutyens’s intervention in March 1893 in securing Tweed the commission for a bas relief for the gable of Groote Schuur in Cape Town, the house designed for Cecil Rhodes by Lutyens’s friend Herbert Baker. The panel was to depict the landing of Jan van Riebeeck, the first European to land in South Africa at the beach next to Table Mountain. Collie, (possibly also at Lutyens’s suggestion) supplied Rhodes with antiques and art for Groote Schuur and in 1895 moved out to South Africa to supervise the decoration. This led to the purchase of other works by Tweed; a statuette of Robert Burns, a free standing figure of Riebeeck and a memorial to the Shangani Patrol which had been wiped out in the Jameson invasion of Matabeleland. In 1897 Cecil Rhodes, as Prime Minister of Cape Colony, was in London to give evidence at a government enquiry into the Jameson Raid. Already working for Rhodes, the sculptor was the only artist to ever have the opportunity of portraying this great imperialist from life and the townspeople of Bulawayo asked Tweed to design a statue of Cecil Rhodes which is in Bulawayo.

Relations with Rhodes were often strained and Tweed’s collaboration with Baker on the Shangani Memorial did not end happily either, but in this period Tweed became established as an important artist. Contact with Lutyens continued and a letter dated 1921 from him survives in the Tweed Archive.

Rhodes’s sittings for Tweed had a serendipitous outcome; he introduced him to the Conservative MP who was on the government committee, George Wyndham, scion of Clouds and at the centre of the society group known as the Souls. This introduction encouraged by Detmar Blow, who was a ‘Souls architect’ led to many portrait commissions, executed very much in the style of Rodin. Then there was his devotion to promoting Rodin in England and securing his gift for the Victoria & Albert Museum which placed Tweed in the heart of the art establishment.

Too old to serve in the First World War, Tweed became a war artist and visited the battlefields. Sponsored by another South African, Ernest Oppenheimer, he was asked to submit a design for the Cape Town War Memorial which was not carried out. His time in Flanders was not wasted. In the next 24 years Tweed produced nearly 20 war memorials and sculptural portrayals of soldiers. One wonders how often the paths of Tweed and Lutyens crossed carrying out their sad work in the 1920s.

This detailed study of John Tweed restores him to his proper place in the history of early 20th century British sculpture and gives us another glimpse of the Lutyens circle. Nicola Capon, Reading Museum, Spire Books and the Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art who supported the venture should be congratulated.

Janet Allen