A friend remembers Derek Lutyens

In Memoriam

Sir Robert Clark

Many members will have heard with regret of the death of Sir Robert Clark. Recently published obituaries testified to his distinguished career, including his wartime adventures and his many subsequent accomplishments and interests. Members of The Lutyens Trust will remember him with gratitude and affection as the generous and patient host, together with Lady Clark, for the many visits by individuals and groups to Munstead Wood, the house which, perhaps more than any other, was responsible for launching the career of Edwin Lutyens. Sir Robert will be greatly missed and our sympathy is with Lady Clark and the family at this sad time.

Martin Lutyens

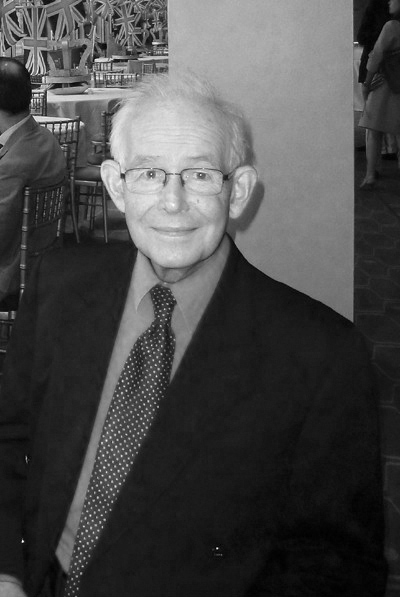

A friend remembers Derek Lutyens

Derek Lutyens, who died of cancer on 12th September, was a great nephew of Sir Edwin and quietly proud of his family’s heritage. He and his wife Jane regularly attended the Trust’s annual Christmas lunch and there can be few significant Lutyens designed properties in the UK and abroad not visited by them. Derek played a prominent part in the Trust’s visit to New Delhi in October 2003, ably assisting Charles B. Lutyens and Paul Waite, the delegation’s leader, and giving a memorable interview on the city’s largest radio station. Readers of this newsletter may also recall that, in the summer of 2011, he organised and paid for the reconstruction of the vandalised monument that marks the grave of his uncle and namesake, Lieutenant Derek Lutyens of the RAF, who was killed on a test flight in 1916. The monument, with its winged RAF logo, was almost certainly designed by Sir Edwin and is close to the graves of the architect’s parents and his devoted nurse in the churchyard of Thursley Parish Church in Surrey. The village, which contains the house of Sir Edwin’s parents as well as several examples of his work, has been, in Derek’s own words, “something of a mecca to the family.”

By an almost uncanny coincidence, I also have a family connection with Thursley: one of my uncles lived there in the ‘40s and early ‘50s and is commemorated by a stained glass window in the church which overlooks the Lutyens graves. This connection, which led Derek and me to make regular joint pilgrimages to the area, is just one of many that helped to forge our lifelong friendship. First contacts were made during our childhoods in Norfolk – with his formidable memory, he could recall attending my second birthday party – and became ever more frequent and rewarding when we both sought careers in London and eventually settled there to bring up our own families.

During his early years, Derek was brought up by his grandparents and mother Meintje as his father Patrick was away, first as a POW in Germany and later as an Adjutant General in the Far East. Educated at Wellington, where he acquired his love of history and literature, Derek came to the capital, after a series of unfulfilling jobs in the provinces, determined to be a writer. Unfortunately, his sharply observed short stories failed to find a publisher and eventually, after much soul-searching, he set sail for Canada and McGill University.

On his return to London, he set out to make “a reasonably comfortable living in the city.” He worked for Barnato Brothers, became a qualified Chartered Secretary, and moved to Robert Fleming. Here he found his metier, handling several important charity accounts until his retirement in 2000.

He reveled in retirement, pursuing his many interests and working for several good causes. He read more than ever, increasing his encyclopedic knowledge of history and literature. With Jane, he indulged his loves of opera, country walks, horse racing and foreign travel. Their house in Clapham was, as always, a hub of hospitality for all their friends. He joined the Friends’ Committee of Dulwich Picture Gallery, became trustee of The Institute of Marine Engineers and of The School Mistresses’ and Governors’ Benevolent Institute, treasurer of the London Trust and, despite not being keen on gardens except as places to read, treasurer of Chelsea Gardens Guild. Best of all, Jane and he appreciated holidays and other times spent with their close family: daughter Emily, an artist and graphic designer married to David Koskas and mother of Alice, son Robert, a palliative care nurse and daughter Sarah, who has followed her father into the city.

After his death, Jane received nearly four hundred letters of condolence. Friends and colleagues wrote about Derek’s many lovable qualities, in particular his great loyalty to people and causes, his legendary hospitality and generosity and his warmhearted companionship that was spiced by a wonderful sense of humour and appreciation of the ridiculous. Many mentioned his impeccable good manners and, as a neighbour put it, “the marvelous way he made you feel better about yourself whenever you met him.” I know that I shall miss him for all these reasons, never more than on pilgrimages to Thursley which I must now make without him.

Nigel Begbie

Professor Mansinh M Rana

Professor Rana was the Lutyens Trust’s Patron in India for many years and, in that capacity he acted as our eyes and ears in Delhi, alerting us to conservation issues and to threats to Lutyens’s Delhi from developers. He was always most helpful and a valued friend to many Trust members.

This obituary, re-printed here from the November issue of Architecture and Design in India, was written by Vivek Sabherwal, a practicing architect in Delhi who also teaches at the Vastu Kala Academy.

Professor architect Mansinh M Rana was one of the few first generation architects of Independent India. He was also the first Indian architect to have studied architecture at the unique school founded by Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin.

Professor Rana had many a story to tell from his bounty of experiences of a well-lived life. He was never short of an anecdote or life’s moments to share, when he was in company, which he was never short of either, given his colourful, vibrant personality. His youthful banter ensured that the young, taking a tip or two from his life’s vast experiences, surrounded him. His stories from his days at Taliesin have been part of every lecture that he gave.

My family’s association with Professor Rana precedes my birth. My father and uncles were his students at the Delhi Polytechnic (now merged with the School of Planning and Architecture), where he was invited to teach, after he returned from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in 1951. Some of his other students who have made a mark in the architectural fraternity were Raj Rewal, Ravindra Bhan, Ram Sharma, Ajoy Choudhury, Shiban Ganju among such others. Professor Rana was a teacher for many years before he was appointed by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru to the Central Public Works Department to design the National Theatre of India. He also designed a residence for Pandit Nehru at Teen Murti Bhavan. Unfortunately, both these projects never saw the light of day. Professor Rana had several other important stints with the New Delhi Municipal Corporation as well as the Ministry of Works and Housing. Some of his significant works include designing the 300-acre Buddha Jayanti National Park and Monument at New Delhi, Nehru Planetarium, Nehru Library, Shanti Van Memorial for Pandit Nehru and Vijay Ghat for Lal Bahadur Shastri, along with a few international pavilions. His work was duly recognised and he was awarded the Padma Shri in 1967. When M Rana returned to India in 1951, he was the first architect to initiate the concept of landscape design as related to environment instead of ‘horticulture’ as generally practiced till then.

Professor Rana shared Frank Lloyd Wright’s ideology that everyone should go out into the world to seek and carve out his own path. People have known him, not only as an eminent architect who has held high positions but a fearless one too, who was not afraid of speaking the truth.

However, I would like to share my observation of some of his humane virtues. During the 1980s, when India was shaken by the ghastly kidnapping and murder of brother and sister Sanjay and Geeta Chopra, Professor Rana, a sensitive man, wrote a passionate letter to their parents and offered them two saplings, one of a tree called ‘Arjuna’, the other of ‘Harshringar’, the former symbolising solidity and bravery and protection of a sister while the latter for everything that is fragrant, beautiful and full of promise in life. Being close to the Nehru-Gandhi family, it is said that once when the renowned painter M F Hussain, a good friend of M Rana’s, wanted to show his work to Mrs Gandhi, he requested M Rana to arrange a meeting. Incidentally, Hussain referred to M Rana as ‘Maharana’. Professor Rana and Mr Hussain drove to the PMO where he showed his works to Mrs Gandhi.

Professor Rana knew everyone in our family and always made his fondness for ‘Masala Gur’ (jaggery mixed with spices – brought specially from Punjab) and ‘Sarson ka Saag’. His animated appreciation of this gesture will live like a cherished memory forever.

I will remain indebted to him for his guidance in joining the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture. Before leaving for Taliesin in 1992, I met him, as my anxieties and apprehensions about Taliesin life were far too many. He assured me that it was the right step for me, and later when I had joined Taliesin, I saw him again at the Taliesin Fellowship Reunion at Wisconsin in 1992. He was always fondly remembered by other Taliesin alumni, and shared many moments of his time during his apprenticeship with Mr and Mrs Wright. His insights into those times have been an invaluable contribution to my learning and understanding of Organic Architecture.

The singular factor that makes M Rana so special is his contribution to education in architecture. In 1989, along with architects C P Kukreja, J R Bhalla, Satish Grover and Ranjit Sabikhi, he established the Sushant School of Art and Architecture in Gurgaon with the support of Ansals Group of which he was the Dean Emeritus. He wanted to impart quality education to young minds, and worked tirelessly towards his goal. He wanted to inculcate values of self-reliance in young students. He was always deeply involved with the students and encouraged them to take off for unexplored areas of the thinking process and pull out expression not tried before. He was involved with the school till he breathed his last.

I have heard M Rana talk on several occasions, and his talk was never straight-jacketed; he spoke freely without mincing words. He was a remarkable man; an architect, philosopher, educator and an environmentalist. At the age of ninety, just before he passed away, he did not think he was old, and was busy working. He was indeed an architect of the soil.