Sullingstead

Summerhouse at Sullingstead

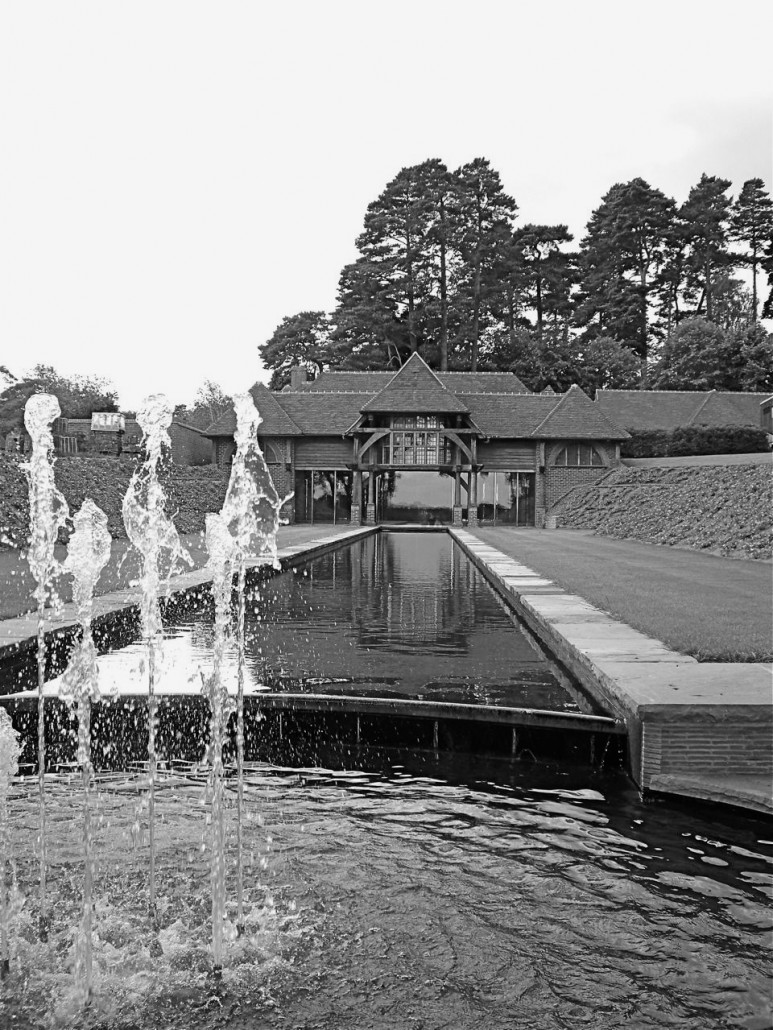

Poolhouse at Sullingstead

Photographs by Michael Edwards

Sullingstead Restoration

Autumn 2010

Sullingstead – now restored, this is one of Lutyens’s most celebrated early country houses, dating from 1897, but best known as a project he returned to with later (1903) additions, famously in an uncompromisingly different style for the music room, changing from half-timbered, tile-hung Surrey vernacular to high -windowed Georgian.

The house, like too many of his works, suffered the collateral damage that inevitably results from many changes of ownership, with consequent alterations diluting the changes made by Sir Edwin himself. The loss, for example, of major chimneys, staircases, fireplaces, main entrance porch and important garden walls, together with the addition of French windows, passageways and numerous outbuildings, has disappointed visitors but the present owner, as well as returning the house to its former character, re-constructing missing chimneys, fireplaces and so on, entailing a good deal of forensic research by his architect, decided to replace modern outbuildings with more appropriate forms.

It must have been in the late 1980s when I originally visited Sullingstead, then called High Hascombe for a time, and, having put away the photos taken, I had not given the house a great deal of thought until being offered a commission of refurbishing it for new owners. Then, comparing the photos with those published in 1913 by Country Life (Houses and Gardens of E.L. Lutyens by L. Weaver), clearly a large number of important features had disappeared – just about every one of the views published at the time lacked key elements…..but we were fortunate in having a client eager to restore these items!

Completed last year, the house is now recognizable again – for example, with the front door always sensibly on the north side, the focal point at the front of the house: the entrance porch that Lutyens used to draw attention to it as one approached the house down the hill, had been removed, possibly due to condition faltering in the weather here on this exposed hillside site. Peering at no doubt the original architect’s drawings that, like a lot of his otherwise missing plans, had been miniaturized for publication in 1913, as well as box brownie photos taken by a housekeeper many years ago, we were able to detail this precariously-located feature so that it would serve its purpose for a much longer period. Chimneys – very substantial ones – were missing too, and the composition, with its two Lutyens extensions in place by 1913 (the kitchen wing and the music room), had been upset by such tall brick features having been removed, particularly the main end chimney in Lutyens’s little sketch that he sent proudly to Lady Emily, remarking on how pleased he was with the amount of work he was doing that particular day in January 1897: “all your doing” as he put it.

French doors, but also a very prominent gable that had replaced the two southfacing dormers, had spoilt the iconic music room addition. Weatherboarding details were changed to tile hanging and together with this over-large projection at roof level, Lutyens’s composition was much changed.

Brick-flanked bay windows to the dining room, too, were missing and so were the two main staircases, both having been replaced. These features, again, were unravelled and restored from the plans in Weaver, helped by two remaining newel posts and kite-shaped changes of level in the foundations, convincing us that Sir Edwin had indeed used a spiral stair down to the music room, and not the more recent “dog-leg” form!

At first floor level the disposition of the originally planned dressing rooms and bedrooms was fortunate (as we have found in other Lutyens houses) in allowing adaptation to current family needs and, though in need of slight adjustment of layout here, like the ground floor, this house shows how, despite the passing of more than a hundred years of family life, it can still perfectly suit present family needs into the future.

Enhancement of interior spaces by designer John Minshaw, whom we invited to join us, has made the changes all the more enjoyable and, working with John, we have added a pool-house on a site near the house, discreetly connected underground to avoid compromising the history of the house, celebrated not only as a prime example of Lutyens in the Surrey vernacular but for being one of the sites that he came back to with characteristic genius. The new pool-house, while externally a tile-and-timber essay in the vernacular, is inside anything but the “flooded barn” of estate agents’ presentations; having given the designer a shell to work within, the result is a very fine exercise of detailing in white materials, bright metal and water, complemented by the broad water-filled rill which we excavated outside – not of Taj Mahal canal dimensions but I do remember trying to find out its proportions!

While the exterior of the pool-house reflects the way Lutyens took every advantage of oak structurally, we re-installed the kitchen and scullery at the east end of the house, but now provided with new sequence of arches in an oak frame of a similar kind but supporting the original gabled roof form, so as to make for a more lofty interior now in place of the previous modest ceiling heights, further enhanced with a spectacular kitchen table made for the space by Candia Lutyens (along with other furniture elsewhere in the house). The missing kitchen stove recess and surrounding massive chimney of Lutyens’s design had gone and with the benefit of the fine old Country Life archive photographs and the 1913 plan illustrations, this is now back in place.

Complementing the house at the outset was characteristically an element of Jekyll planting, much of it surviving but now having received due attention to detail. But there were other areas that had succumbed to the economies of lawn or gravel and a substantial garden wall on the west side had altogether disappeared. We were fortunate, therefore, in the arrival of two drawings prepared for Lutyens by Raffles Davison, recently purchased from a previous owner, and these gave us valuable information on the setting out of the beds which were later photographed by Country Life. We think these drawings of 1904 were prepared for Charles Archer Cook, and showed how the new gardens might look alongside the house and by extrapolating borders and steps off the drawings by calculation, the landscaped garden on the west side of the house is now reinstated with a very good degree of authenticity, including a pergola frame, even if it had never materialised beyond the artist’s pen and paper.

On the other hand, the garden to the east of the house survived as little more than a terrace of rough grass, planted at one time as a part of the kitchen gardens. There, a 1960s wire-netted and shingle-clad aviary was barely surviving and for this part of the site, bearing in mind the east end of the plan was originally set out within the house as the service element of the arrangement (kitchen, scullery and servants’ hall), a better arrangement was now in order to suit what is these days very much part of the family domain, and needing a better outlook than offered previously to kitchen staff. The result of these observations, and in place of the aviary, is a new garden summer-house, loosely reflecting features of the distant music room on the same axis and complemented by the now flourishing rose garden layout – the building has a number of Lutyens references and so we were quite surprised to see how much by coincidence it resembled the geometry of Wyatt’s newly restored building for Earl Darnley, which we had not come across before!

Needless to say, while reinstating the house to its original form, removing the palimpsest of a passing century, we came across some interesting features, like the original west-facing windows hidden in the fabric of the music room extension, and in the roof space, set out on the boarding beneath the roof tiling, a full-size setting out drawing of what must be a Lutyens newel post – not that of Sullingstead but probably of one of the parallel projects (we photographed it before completing the lining of the roof). We also came across lime-wash-painted external brickwork elsewhere where other elements added by Lutyens and the Cooks had covered what must have been another external wall on a different part of the house.

There are many of these early houses we have worked on that have suffered somewhat from changing family needs but what is clear is that the generous organisation of spaces; the sensitive siting of the houses, as well as the considerable care taken in construction (obviously down to Lutyens and his having as well the right sort of clients – in most cases!), all go to make for a good future for his buildings, and what we find now is that the latest generation of families taking up ownership of these masterpieces seems more able to provide the care and attention necessary than ever before – indeed it appears to me that the families keen to own these magnificent properties are somewhat akin to those who commissioned them in the first place, and are able to prioritise necessary works in a way that the Trust will continue to welcome.

Michael Edwards

Note: Members may be interested to know that there is an article about the Sullingstead restoration in the current (September) issue of House and Garden magazine.

Andrew Barnett

Andrew Barnett