Edwin Lutyens’s Rashtrapati Bhavan, Jaipur column and Mughal screen, New Delhi. Photo © Stephen Williams

Special India Edition

A Record of the Trust’s India Tour, 2017

Forward by Martin Lutyens

As promised in the Spring Newsletter, this current edition is dedicated to the Trust’s marathon study tour to India in November, 2017.

There are many people to thank for making this a success. Paul Waite and Graham O’Neil, who together planned the itinerary; Paul who organised access to the many sites we visited; Rebecca Lilley who supported Paul and assisted with travel and administrative arrangements; the participants who managed not to wilt despite the succession of early mornings and long daily journeys; all those who have contributed articles; and those who photographed our adventures, especially Stephen Williams who, with his array of cameras, is responsible for the majority of the illustrations; and last but far from least, our friends at INTACH and others in Kolkata and Delhi who helped us to access some of the most important buildings.

The tour’s scope was ambitious and even writing and producing this Newsletter in a form that does it justice has been a massive task for the contributors, especially Edwin’s great grand-daughter, Nicole Pallant, who has been helping our Editor, Dominic Lutyens, with assembling the copy, selecting images and proof-reading.

Because of the much larger number of words and images than usual, we have used a correspondingly larger format to keep down the number of pages and make it easier to read. The Newsletter will revert to its usual form from the next edition.

I hope you will enjoy this report and find it worth waiting for. For another and very engaging perspective of the tour, we will also be posting on the Trust website the journal which Nicole kept each day as the tour progressed.

Map created by Rebecca Lilley

Introducing the Tour

By Paul Waite, the organiser

I sometimes feel an old hand at organising tours and yet, whenever we’ve travelled to India, it’s been an exciting, fresh challenge from the moment we first had the idea to our return to England, with a mixture of relief and satisfaction at mission accomplished. Every time I’ve been amazed by our hosts’ and facilitators’ generosity in allowing us into such highly protected buildings. On our very first visit, organised by Roderick Gradidge, we travelled to all the Indian sites that Edwin Lutyens was instructed to see after he was told that he had to design in the Indo-Saracenic rather than the Classical style as he had wished.

Although it’s hard to imagine a Lutyens or Baker building in the Indo-Saracenic style, the influence of this journey on their work at New Delhi is clear: as AG Shoosmith — Lutyens’s resident representative at Delhi from 1920 to 1931 and architect of the Garrison Church, St Martin’s there — put it: “Western art, adapting to Indian needs, has borrowed from Eastern forms and combined them with its own so easily and naturally as to suggest that the ideals of East and West, though widely different, are complementary”.

After the Gradidge tour, all the subsequent Lutyens Trust tours to India had concentrated on New Delhi alone. Of course, there is at least a week’s worth of Lutyens and Herbert Baker buildings with other historic sites to visit in New Delhi, easily expanded by looking at pre-New Delhi buildings and at those of the many 20th-century architects who worked there. So much so that I told my trustee colleagues that the fourth India tour, in 2007, would be my last. In saying this, and with the additional great pleasure of co-organising, with Margaret Richardson, an exhibition of Lutyens’s work at the British Council in New Delhi, I felt as many members as possible should have the opportunity to join the tour: eventually we numbered 80. With organising access to the buildings, the large number of participants and mounting the exhibition, it became the most complex and successful tour yet. And when it was over, I felt I had finished with tours to India!

Every year, however, the Trust fields many enquiries from travellers wishing to gain access to Lutyens’s and Baker’s New Delhi buildings. Additionally, new members regularly ask the Trust when we will be visiting New Delhi again. And so I began thinking in 2013 that we might visit again. I had always been fascinated by Lutyens’s designs for the Classical bungalows on the vice-regal estate and the elegant Classical bungalows that were built in their hundreds by the Public Works Department in New Delhi under his supervision. As always with his designs, they looked simple but were so much cleverer than they seemed.

Additionally, in the back of my mind was a series of engravings of 18th-century Calcutta, which was described as a “City of Palaces”. Among these palaces were Classical 18th-century bungalows that bore striking similarities to Lutyens’s New Delhi designs. So I set out to research whether any of these bungalows had survived, thinking that Lutyens might have seen them when passing through Calcutta (now Kolkata) or when he stayed there with his brother-in-law, Lord Lytton, when he was Governor of Bengal between 1922 and 1927 and, briefly, Viceroy in 1926. Indeed, there was one very important bungalow still standing — the 1863 Flagstaff House at Barrackpore, formerly the official residence of the Governor’s private secretary and later the British Commander-in-Chief, now residence of the current Governor of West Bengal. Then I wondered how much the immense 18th-century vice-regal palace (now called Raj Bhavan) at Kolkata — modelled on the magnificent Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire, seat of the Curzon family — had influenced New Delhi’s Viceroy’s House. And I thought of Le Corbusier designing his capital at Chandigarh after the Second World War.

In looking into various provincial capitals between Kolkata and Delhi, I not only found that ruined Classical buildings in Lucknow were preserved after the Indian Mutiny (also known as the Sepoy Mutiny) of 1857 but that the new administrative buildings in Patna had been designed in a Classical style in 1916 after Lutyens had been told to design in the Indo-Saracenic style. And so a thread appeared: we could look at 20th-century capitals of India, starting at Kolkata and moving across the country to the provincial capitals of Kanpur, Lucknow, Patna and Chandigarh, to compare buildings there with their counterparts at New Delhi and the Raj summer capital of India, Shimla: and taking in significant Buddhist, Hindu and Mughal sites along the way, as Lutyens and Baker had been told to do just over a century before.

It took until 2017 to plan and organise the tour but it turned out to be a rich vein of architectural history. I’m most grateful to everyone who participated; assisted with gaining access to important buildings, and subsequently contributed in words and/ or with photographs to this record of the tour.

Group photo of Lutyens Trust members on the India tour outside Government House, Barrackpore. Photo © Stephen Williams

Barrackpore, 4 November

By Peter Verity

Our tour revealed how the layout of the military and civil structure, organisational hierarchies and contemporary influences determined the form and architecture of New Delhi. There were some key sites we visited on the way, starting with Barrackpore (a name possibly derived from the English word, barracks).

It was perhaps appropriate in our search for Lutyens’s Indian path towards the planning and design of New Delhi that we should begin our journey at Barrackpore on the banks of the Hooghly River, 15 miles north of the centre of Kolkata. In 1775, the city, then known as Calcutta and the birthplace of the East India Company, was the first military cantonment in India and remained the symbolic seat of military power in the country until New Delhi became the capital. Barrackpore became, in its organisation, the model for the cantonments that followed. These were characterised by a grid pattern of streets (for the easy deployment of troops and artillery), later becoming tree-lined avenues of detached bungalows with a hierarchy of residential areas for military and civilians interspersed with defensive tanks which segregated the rulers from the ruled. At its focus is a large rectangular barrack square around which are strictly separated quarters for officers and soldiers and a zone for the bazaars away from the cantonment. Such separated zones became a characteristic of all other cantonments in India.

Following the Indian Mutiny of 1857, cantonments modelled on Barrackpore became the norm. These separate defensible towns for Europeans, segregating the rulers from the ruled, were divided along civil and military lines with their clubs, churches, racecourses and a rigid hierarchy of zones all found at a distance from existing towns. Lutyens’s New Delhi became the ultimate expression of this evolved cantonment planning.

In 1813, at Barrackpore Lord Wellesley began the building of Government House — the British Governors’ General residence — set in a sprawling estate as a summer retreat and the construction of a tree-lined processional route linking Barrackpore to the centre of Calcutta. Designed by Captain Thomas Anbury, Government House has a Tuscan entrance portico with a shallow pediment that overlooks the river and collonaded verandas enclosing the other three sides. This design somewhat echoes the central body of Government House in Calcutta. It was a delightful surprise for us to find that the house and the Mughal bath from Agra in the garden were now being restored by the police authorities who were eager to hear our group’s advice as how best to proceed.

Of the original staff bungalows possibly the most significant is Flagstaff House, residence of the Governor’s private secretary and later Commander-in-Chief (pictured, left). This is a simple stuccoed Palladian bungalow embellished by a Tuscan entrance portico with a second portico in the form of a projecting loggia on the garden front, overlooking the river. We understand that this may have acted as a model for the Lutyens-designed staff bungalows at New Delhi. Screening Government House from Flagstaff House is the Temple of Fame of 1813 designed by GR Blane. It has hexastyle Corinthian porticos at each end and colonnades to the flanks as a memorial to the dead of the 1811 conquest of Java and Mauritius. The latter contains a tablet commemorating the 1843 Gwalior Campaign. Around the buildings now stand statues of George V and Viceroys, Governors-General, Governors, military leaders and politicians that formerly graced Calcutta.

In Barrackpore we also visited the 1831 St Bartholomew’s Church (pictured), where there are poignant military monuments and, next to the river, there is a similarly moving and distinctive memorial to Lady Charlotte Canning, who died in this neighbourhood in 1861. Now guarded by the equestrian statue of Lord Canning, it’s a replica of that of George Gilbert Scott, which we were to see later at St John’s Church, Kolkata.

Calcutta/Kolkata, 5 November

By Peter Verity

The mutiny at Barrackpore led to the nationalisation of the East India Company and from 1858 to Calcutta becoming the seat of the Viceroy and from 1877 to 1911 the Imperial Capital of India. Our group was given the great privilege of visiting Government House — now Raj Bhavan, residence of British Governors and Viceroys until 1911. Designed by Charles Wyatt on the lines of Kedleston Hall, it is set in a large garden compound at the north end of the maidan, Kolkata’s vast park, and was the focus for the entire development of Calcutta. It was built in the belief that “India should be ruled from a palace and not a counting house; with the ideas of a prince, not those of a retail dealer in muslin and indigo”. When the capital of India moved from Calcutta to Delhi, Lutyens was charged with replacing this fine palace with the Viceroy’s House, now Rashtrapati Bhavan.

Access to the compound is restricted but the building’s main external features can be seen from the surrounding roads. It comprises a central block with quadrant corridors linked to four corner wings. Set behind a two-storey collonaded veranda is a domed bow to the garden front and an Ionic portico to the symbolic entrance, the actual entrance being via a portecochère under the approach steps. The plan works particularly well in the Bengal climate since it encourages breezes to ventilate the accommodation areas, which are arranged on two floors over a raised basement.

The principal area of its interior is the central Marble Hall, an all-purpose space for assemblies that leads directly to the Throne Room, which still contains Wellesley’s throne and that of Tipu Sultan, a ruler of the kingdom of Mysore. On the floor above is the Ballroom or Banquet Hall lined with Doric columns and chandeliers from officer Claude Martin’s palace at Lucknow (more of which later).

The Viceroy’s private apartments were in the independent southern wings, the council chamber and secretariat offices in the northeast and west wings. The services were partly in the basement but most of them, including the kitchens and stables, were outside the compound in nearby buildings.

This building symbolising the seat of power — together with its organising principles of an elevated “piano imperial” with separate wings for the complex organisational and functional hierarchy, servicing access routes on the ground floor as well as accommodation over two floors behind a unifying giant collonaded veranda — are all attributes of Lutyens’s replacement palace for the Viceroy at New Delhi.

Kolkata, 5 & 6 November

By Nicole Pallant

After Barrackpore, we spent two days in Kolkata. Unlike many Indian cities colonised by the British, Calcutta was originally an area of small villages on mudflats beside the Hooghly. By 1773, it had become and was to remain the first commercial and political capital of British India until 1911, when the capital moved to Delhi.

We began our tour with a visit to Park Street Cemetery (pictured). One of the earliest non-church cemeteries in the world (and a Christian one in the 19th century), it opened in 1767 and was in use until around 1830, serving as a burial ground for expatriates who lived there. The enclosure is undergoing restoration, a daunting task as it is enormous, containing around 1,600 weather-worn mausoleums, memorials, pyramids, catafalques, pavilions and obelisks. The different shapes and sizes of the monuments, many immense and grand, are tightly packed together yet tree roots and trunks growing around them threaten to displace them. They are cloaked in moss and collapsing under a jungle of overhanging branches. Yet their inscriptions — detailing many who died young of disease — were visible and a sombre reminder of the human cost of the Empire.

From Park Street Cemetery we drove to the Victoria Memorial, built between 1906 and 1921 by Sir William Emerson (1843-1924). Dedicated to the memory of Queen Victoria and history of British rule in India, it was commissioned by Lord Curzon as the ultimate symbol of imperial rule in India. It is faced in the same Makrana marble from Rajasthan as the Taj Mahal and, rising high over the southern end of the maidan, it dominates the city centre. It certainly succeeds in demonstrating the grandeur and stateliness the Colonial British wanted to show off. Inside is a wonderful assortment of paintings, statues and memorabilia of the Raj and an exhibition of its history.

From here, we drove along Chowringhee Road, a main thoroughfare where in the mid 18th and 19th centuries Englishmen built imposing houses, hence Kolkata’s moniker, “City of Palaces”. Here, as in other areas, we saw the crumbling remains of these architectural gems that fell into disuse and ruin after Independence. Today many are barely held together by a tangle of interwoven telephone and electricity wires or trees that appear to stitch the bricks together while in fact creating irrevocable damage. Our next stop was the Indian Museum, a palace built in 1875 by Walter Granville with a central quadrangle enclosed by Ionic columns. It is the largest, oldest museum in India and houses geological, archaeological and zoological artefacts, textiles and Mughal paintings. Of special interest were the polished red sandstone railings and gateway of the Buddhist stupa discovered in Bharhut in 1873 and similar to those at Sanchi, which were the inspiration for Lutyens’s design of the central dome of Rashtrapati Bhavan.

A packed lunch awaited us back on the bus. In the afternoon we visited the Marble Palace, the most extraordinary home of a Babu family (middlemen between Indian and English traders) who became immensely rich. The mansion gained its name from the marble wall panels and floors made from 126 types of colourful Italian marble. Built in 1835 by Rajendra Mullick, it continues to be a residence for his descendants. A feeling of nostalgic decay pervades the slightly forlorn but grand interior which houses, among other objects, Murano chandeliers, 12-ft high Venetian mirrors and reproductions of Renaissance sculptures and paintings by Sir Joshua Reynolds and Rubens. A fascinatingly eclectic, sometimes kitsch mix of artefacts — Baroque curios, Greek, Roman and Indian sculptures and objets d’art jostling with Biblical figures — add to the novelty and whimsical eccentricity of the palace.

Outside its iron gates, we stepped back into the noisy hubbub of Kolkata and into small side streets towards Tagore House. Compared with the Marble Palace, Tagore House was a paragon of simplicity inside. Built in 1784, it has become a shrinelike museum to India’s greatest modern poet Rabindranath Tagore, who was born here. He was the first non-European Nobel laureate and became a venerated religious leader.

On our second day in Kolkata, we began with a walking tour of Dalhousie Square, now named BBD Bagh. It’s the oldest square in the city and lies at the heart of this area once covered by the original Fort William before the new fort was erected to the south of the city between 1757 and 1770. It is centred on the water tank, Red Tank, also known as Lal Dighi, that provided the city — some of whose earliest and grandest civic buildings are in this quarter — with drinking water. Still in use, these provide a glimpse of Calcutta’s living British heritage. Our walk brought to life the story of the growth of Calcutta from its early years to modern days where the indigenous humanity of India is interwoven with the streets and facades of these buildings — makeshift homes where clothes lines are strung across recessed arches of imposing old buildings or between lampposts. Collapsible charpoy beds lean against railings, with cooking utensils and plastic bags full of possessions and food suspended out of reach of stray dogs.

Our walk started early and the neighbourhood was waking up in a hive of activity as we strolled along the streets. Men squatted on the pavement next to boiling aluminium cooking pots, preparing their breakfast. Refreshments were being prepared for people who had travelled in from the country, ready to take their cases to the High Court. Countless stallholders under bamboo-supported plastic awnings were cooking roti and dahl on clay stoves or brewing cardamom-scented tea poured steaming into terracotta cups (thrown to the gutter after use). Antique sugarcane mangles with rusting wheels and cogs served cups of juice. A fish-seller on his haunches gutted fish by the road. Men in loincloths lathered themselves from top to toe and rinsed off at water pumps. While not wanting to miss one moment of the activity around us, we had to take great care not to trip over missing paving stones or lose a foot down a pothole!

Among other monuments and buildings, we passed the High Court, inspired by the medieval Cloth Hall in Ypres and one of the city’s most important Gothic edifices. Outside, a dusty old typewriter on a rickety wooden table was ready for its owner to type up the cases for those due to present them in court. We also saw Metcalfe Hall, raised on a solid basement with 30 huge Corinthian pillars and inspired by the Tower of the Winds in Athens; the General Post Office with its grand dome and Corinthian pillars on the site of the notorious, much-disputed Black Hole of Calcutta of 1756; The Writers’ Building on BBD Bagh, originally the office of the clerks of the East India Company, which now houses the secretariat of the State Government of West Bengal; St Andrew’s Church, based on James Gibbs’s St Martin-in-the-Fields in London and the only Scottish church in Kolkata, and St John’s Church (originally called the “Stone Church” so rare was the use of stone in the early days of the Empire), also modelled on St Martin-in-the Fields. This has later additions of a carriage porch and Corinthian capitals to the Doric columns in the nave and collonaded verandas designed to reduce glare. Paved with blue-grey marble, the interior was light and airy. On the walls hang many memorial tablets, statues and plaques, mostly of British army officers and civil servants. Once at the central altar and now in the south aisle hangs German artist Johan Zoffany’s large painting of 1787, The Last Supper, which depicts famous Kolkata residents in the guise of the Apostles.

In the graveyard are many historical sights, for example, the Rohilla Monument. Constructed in 1794 to commemorate the East India Company men who died fighting the Rohillas in Northern India in the early 1770s, it is a domed cenotaph based on Sir William Chambers’s Temple of Aeolus at Kew Gardens. Close by is the tomb of Job Charnock (1630-1692), probably erected in 1695 and one of the earliest surviving British monuments in India. Here, reads its inscription, Charnock — generally regarded as the founder of Calcutta — “sleeps undisturbed amid the dust and din of the town he called into existence”. The 1902 obelisk-style marble monument to those who died at the Black Hole of Calcutta was moved here from The Writers’ Building. The monument I found most curious was the circular temple-like tomb of Frances Johnson (1725-1812). Known as Begum Johnson, this grand old lady of Calcutta lived to 89, married four times and bore six children. An epitaph inside the mausoleum describes her entire life, summarising her marriages and family life.

After a packed lunch on the bus, we had the privilege of a private visit to Raj Bhavan. Many of us had left jackets and clean shoes on the bus to change into after our long morning’s “heritage” walk.

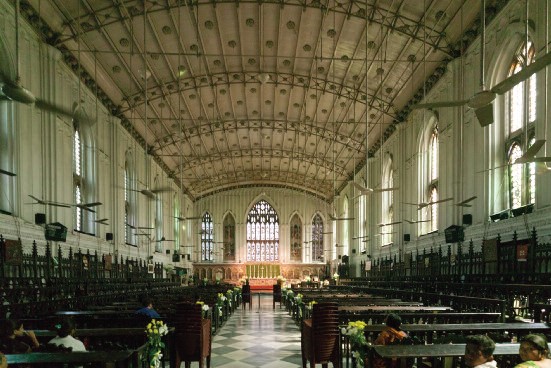

After this memorable visit, we just had time to visit to St Paul’s Cathedral (pictured) before catching our train from Howrah station to Patna. The white interior of this Indo Gothic-style cathedral is open and spacious. There are no side aisles but a large central hall with a curved roof supported by metal trusses. As the cathedral was built on poor subsoil there was doubt that land beneath it could support the weight of columns and arches. I was especially excited to see the stained-glass windows by Edward Burne-Jones. They were commissioned in 1880 as a memorial to statesman and Viceroy of India, Lord Mayo. We climbed the side stairs to get a better look and they are indeed breathtakingly beautiful. I wish we had had more time to explore and study properly the cathedral’s many other statues, monuments, memorials and tablets. Outside it, a portecochère was shading a group of Indian women in colourful saris chitchatting on bright plastic chairs.

Late that evening we arrived at Patna station after an eight-hour train ride. A multitude of porters was waiting to carry our suitcases, which they piled two by two on their heads, balanced atop a narrow twisted turban. As we crossed the bridge over the platform a gigantic mass of insects flitted about the lamps and into our path. We’d also just arrived at the state of Bihar where alcohol is prohibited, so no nightcap to relax us after the day’s exertions!

Patna, 7 November

By Peter Verity

With the partition of West Bengal in 1912, Patna was restored as the capital of Bihar. This new imperial city (the cantonment) was designed by British-trained New Zealand architect Joseph Fearis Munnings in 1911, the year before Lutyens began his work on New Delhi and with similar requirements to accommodate the established spatial structure of European society. While the design and realisation of New Delhi was to take 20 years, the work on the 3-sq mile Patna with its Secretariat and other buildings was largely completed by 1915.

Its planning is Beaux-Arts in style with parallels to Baron Haussmann’s ronds-points — also a feature of the Delhi plan — while its curved roads echo those of the garden-city movement. The great central set piece is the processional route of George V Avenue (Rajpath) flanked by large public buildings and linking Government House with the Secretariat and its tower. As with New Delhi, there are strong parallels with American architect Walter Burley Griffin’s 1912 plan for Canberra. (We were to encounter Griffin later at Lucknow where he had worked extensively to create a modern Indian architecture until his death there in 1936.)

We saw Munnings’s Secretariat, a huge building dominated by its clock tower whose form owes something to Herbert Baker’s Government Building of the Union of South Africa at Pretoria. It also demonstrates Munnings’s quandary as to whether government buildings should adhere to Western Classicism or “a natural type of architecture” and, apart from its Doric portico, there is little that is decorative. The tower has Mughal precedents, uses chajjas (overhanging eaves) as functional elements and is one of the earliest examples of the incorporation of Mughal features into a government building. These represent a sea change in the government architecture of India.

As the light faded, we saw Munnings’s 1920 Government House, now called Raj Bhavan. Here the modern movement is evident, it being “Stripped-back Neoclassical” in Palladian form where decorative elements have been reduced to a minimum. In the centre of the rond-point in front of Government House was the pedestal to Lutyens’s design that had once supported a statue of George V. We’d seen the model of this, with the king in place, earlier in the day, in the

garden of Quila House.

Patna’s residential avenues are, like Canberra’s, arranged in concentric rings with bungalows in large plots with their now mature trees giving solid, three-dimensional borders to the avenues. The city’s planning and zoning reinforced the colonial era’s social order, even to the extent that there is a graduation of the size of residences, from larger to smaller as these move away from Government House.

Like Lutyens at New Delhi, Munnings gave his cities a layout and order that demonstrated the superiority of the Raj. Both self-consciously turned their backs on the apparent illegibility of Indian urbanism and ignored the possibilities offered by contemporary research that revealed the distinctive morphologies of earlier settlements on the subcontinent. Contemporary reports state that by 1915 it was clear that “the New City of Patna was like no other that India had known”.

Before leaving Patna we saw the Golghar, a most extraordinary building; a huge 1786 brick beehive-shaped granary with an external staircase rising to the top (pictured). It was built by the British East India Company as a famine relief measure and can store some 137,000 tons of grain but it was never used.

Nalanda, Rajgir, Bodh Gaya and Sasaram, 8 & 9 November

By Nicole Pallant

Leaving Patna, we headed south towards Rajgir and UNESCO World Heritage Site Nalanda. Once a large Buddhist monastery and scholastic institution said to date from the 5th century AD, it was the most ancient university of the Indian subcontinent. It originally comprised six brick temples and 11 monasteries, arranged on a grid pattern: we saw a section of the immense site with its impressive brick remains of stupas, shrines and residential and educational buildings that still stand proud and demonstrate its former greatness.

A short drive away are the two Son Bhandar Caves, believed to have been hollowed out of a cliff in the 3rd to 4th centuries AD. Son Bhandar means “store of gold”, and legend has it that the caves conceal a passage leading to this treasure. The caves are decorated with small sculpted motifs in relief and delicate statues representing Jain and Hindu gods. Although still a mystery, these caves remain a place of worship as the gold leaf rubbed on some of the beautiful small figures, including that of Vishnu, testified. A rotund holy man wearing a bright orange lungi and stainless-steel watch guarded them together with some best-kept-away-from monkeys, one of which bit a young boy who had unwisely teased it.

Despite a long day of travelling and sightseeing we luckily resisted going straight to our hotel and stopped at Bodh Gaya, another stunning UNESCO World Heritage Site. Considered one of the most important Buddhist places of pilgrimage, it is dominated by the ancient brick Mahabodhi Temple Complex, built to mark the site where the Buddha attained enlightenment beneath a sacred Bodhi Tree. We saw the direct descendant of the tree that sits behind the main temple, its enormous gnarled branches and thick green canopy supported by metal stakes. As we’d arrived well after sunset, the temple complex lit up against the darkest blue night sky, creating a magical contrast that enhanced its mystical aura. We quietly edged our way, together with pilgrims and other tourists, along the main pathway, flanked by votive stupas and shrines that led towards the main temple, and queued at the doorway leading into a hall, then a sanctum, which contains a gilded statue of the Buddha holding earth as witness to his achieved enlightenment. Everywhere pilgrims prayed, performed religious ceremonies, chanted and meditated.

The next morning we made our way towards the ancient city of Sasaram, driving past wooden carts filled with cauliflowers, potatoes and glossy aubergines. Honking and hooting our way along, we slowly advanced through the noisy plethora of vehicles, scooters, rickshaws, men, women, children, dogs and cows crisscrossing the roads in every direction until we arrived at the magical red stone mausoleum of Sher Shah Suri, tomb of the founder of the Suri empire in northern India (pictured). This Indo-Islamic tomb stands on a stepped square plinth in an artificial lake and, from afar, appears to float on water. It is reached via a wide stone bridge and up steep steps cut through the parapet wall. Ornamental domed kiosks surround the main dome and canopies and kiosks stand on each corner of the platform. Under the overhanging roof we could see remnants of decorative glazed tile decoration. Designed by architect Mir Muhammad Aliwal Khan and built between 1540 and 1545, it is stunningly beautiful and tranquil, as if a mirage in a fairy tale. I can still clearly remember the sheer delight of first gazing on it from ashore and the pleasing anticipation of approaching it from the bridge.

A packed lunch awaited us on our bus as we proceeded towards Sarnath to visit the oldest site museum of the Archaeological Survey of India, which houses excavations from the adjacent archaeological site. Stepping into this relatively small museum, we were greeted by the magnificent Lion Capital of Ashoka, adopted as the State Emblem of India in 1947. This museum’s ancient artefacts include many images and sculptures of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas.

Once past a thick haze of pollution that had increased gradually throughout the day, we entered the archaeological site towards dusk. The massive Dhamek Stupa dominates the park and is said to mark the spot where the Buddha gave the first sermon to his first five Brahmin disciples after attaining enlightenment. This imposing brick monument is decorated with lovely stone carvings of leaves, flowers, geometric patterns, birds and human figures.

In Varanasi, 10km south of Sarnath, we arrived at the luxurious Taj Nadesar Palace Hotel with its manicured palm tree-adorned gardens and inlaid marble swimming pool.

Varanasi, 9 & 10 November

by Rebecca Lilley

Leaving behind the charms of Bodh Gaya was hard after our fascinating stay there the night before, but we were all looking forward to seeing our guide Sharad’s hometown of Varanasi that evening. The night would also bring us our first authentic Indian shopping experience. His local knowledge led to him to taking us to a shop called Silk Khazana, and our group was treated to a live demonstration of hand loom-weaving before sitting down to a cup of chai in front of a magnificent colourful, intricate showcase of silk products made in Varanasi. Enthralled, I bought the most exquisite turquoise and gold sari. The city gave us plenty of other opportunities to immerse ourselves in its culture from pre-dawn excursions on the holy River Ganges (pictured) to witnessing the sunrise — alas, it was too smoggy to see the sun — and the famous riverside cremations to walking through the winding narrow streets surrounding the Vishranath Temple, having massages in the hotel and experiencing the evening Aarti ceremony from the banks of the Ganges.

Allahabad, Lucknow and Kanpur, 12-15 November

By Andrew Wilton

Allahabad is one of the holiest Hindu sites. At the confluence of the Ganges and the Yamuna rivers (pictured, left), beneath an impressive fort begun by Mughal emperor Akbar in 1583, is where the Kumbh Mela, held every 12 years, and a number of other festivals at which Hindus bathe in the wide, shallow waters to purify themselves, take place: a ritual that is auspicious whenever performed. We performed it too but only to the extent of being taken out in an — unfortunately covered — boat; from under the awning we could glimpse pilgrims in the river and on the bank, mingling with tourists and souvenir-sellers. There were large flocks of tern on the shining water — apparently migrating birds from Siberia.

In the city, we visited the Khusro Bagh, a 40-acre walled garden around three stately Mughal tombs on stepped platforms, each distinctly different in character and detail but all complementing one another and forming a noble composition (pictured, left). Khusro (also spelt Khusrau) was the son of the Mughal emperor Jahangir and his wife Shah Begum. She committed suicide in 1604 and is commemorated in a tomb designed by Aqa Reza. The interior of the tomb of Khusro’s sister Nithar Begum is painted with exquisite geometric and botanical patterns and, being empty, can be entered and its beautiful decorations enjoyed by visitors (pictured, left). Unlike the other two tombs, it has a square chattri (canopy) rather than a dome. The third tomb is of Khusro himself, murdered in 1622 on the orders of his brother Prince Khurram, who later became the Emperor Shah Jahan. His horse is buried near him.

We also visited All Saints Cathedral, built between 1871 and 1887 to designs by William Emerson, who’d just designed Crawford Market in Bombay and would later design Muir College in Allahabad and the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata. GA Bremner, author of the 2013 book, Imperial Gothic: Religious Architecture and High Anglican Culture in the British Empire, 1840-1870, describes the cathedral as “the most thorough-going and consistent attempt at Tropical Pointed architecture in an Anglican church anywhere during the mid-19th century”.

Emerson was a pupil of architect William Burges, and his cathedral at Allahabad shows the strong influence of Burges’s Saint Finn Barre’s Cathedral at Cork. Built in cream-coloured stone with red sandstone dressings, All Saints Cathedral is at the same time highly inventive, large and spacious. Responding to its tropical setting are ingenious devices for ventilation and shade provided by deep arcades with flying buttresses all round the nave, choir and apse in front of the clerestory windows. This is, perhaps, the most impressive example of the speluncar or cave-like architecture that William Scott of the Ecclesiological Society advocated in 1851 for tropical climates. Although its style is essentially 13th-century Gothic, it incorporates decorative devices borrowed from a Mughal model, the city of Fatehpur Sikri. Emerson intended it to have towers and spires at the west end, but these were not built; instead there is a square tower over the crossing.

Two other idiosyncratic Victorian buildings here are the Mayo Memorial Hall and Muir Central College. The Mayo Hall commemorates Richard Bourke, 6th Earl of Mayo, who was Viceroy from 1869 until 1872 when he was knifed to death by a Pathan convict. It was built in 1879 to designs by Richard Roskell Bayne and is now a sports complex. Its architecture is bizarre. Dominated by a 180ft-high tower, it incorporates a huge hall with a ribbed barrel roof, gables and pinnacles with elaborate wrought-iron ornament and a chunky, battered porte-cochère with a turret attached to odd buttresses in the form of squashed arches.

Also designed by Emerson, Muir Central College was founded in 1872 by the Scottish Orientalist Sir William Muir, author of The Life of Mahomet (1861), who became Lieutenant-Governor of the North-Western Provinces of India in 1868. He was, notwithstanding, ideologically opposed to Islam, and memorably insisted, “The sword of Muhammed, and the Koran, are the most stubborn enemies of Civilisation, Liberty, and the Truth which the world has yet known”. The imposing college, a pioneering example of the innovative, Indo-Saracenic style, was built from 1874 to 1876. Like Mayo Hall, it is dominated by a high tower and boasts a large, decorative dome. We did not have an opportunity to explore the interior.

Our final visit in Allahabad was to the Anand Bhavan, home of the Nehru family, built by Motilal Nehru in 1930. It’s a handsome, not to say jolly, residence — certainly “no Modernist statement”, as Jon Lang, Madhavi Desai and Miki Desai assert in their book, Architecture and Independence: The Search for Identity — India 1880-1980 (1997) — with a small decorative dome and long verandas surrounding it on two floors. It contains a museum dedicated to the Nehru and Gandhi families — Indira Gandhi donated the house to the Indian government in 1970. The rooms are preserved as they were lived in and protected by plate glass. The house is set off by handsome gardens.

Lucknow, the capital of Uttar Pradesh, is an important city that contains substantial monuments of several periods; it was a key location during the Indian Mutiny.

We first visited Constantia, the remarkable house that a freelance French soldier from Lyon, Major General Claude Martin (1735-1800), built for himself and in which he was buried (pictured). He made a fortune that he distributed in his will to many worthy causes, including the two schools, one for boys and one for girls, known as La Martinière, in Lucknow. There is also a La Martinière in

Kolkata and three in Lyon in France. (Some of us had attended evensong with the boys and girls of La Martinière, Kolkata at St Paul’s Cathedral there.) Martin designed the house in Lucknow as his country residence and it was much enlarged after his death. It’s a strange white and red building with tall cupolas surmounted by sculptured figures and topped not by a dome but by a very odd crownlike structure of open, crossed arches. Huge stone lions clamber up the turrets on the perimeter wall; these allude to the supporters of the arms of the East India Company. He was buried in the crypt, with sculptures of mourning sepoys in attendance. They and the rest of the tomb were demolished in the Mutiny but Martin’s bones were eventually restored to the crypt and a fine bust of him stands guard over it instead of the sepoys. Johan Zoffany included his portrait, along with that of his friend, the Nawab Wazir of Awadh, in his painting, Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match, on display at Tate Britain.

Kipling specified La Martinière as the school where Kim was educated, and the whole place is vividly evocative of the Raj. As we drove through its vast grounds, many of the 4,000-odd pupils could be seen on its playing fields, engaged in football, martial arts and gymnastics, often being bellowed at as if by a sergeant major, marching to drums, bugles and bagpipes. Horses were led past us, their stables bearing their names on boards: Grey Goose, Society Delight, Star Perfection, Sapphire… Inside, Anglican hymns and the carol O Christmas Tree were being sung in the stained glass-lit chapel.

Nearby in a garden on the banks of Gomti River stand the ruins of the palace of Dilkusha Kothi, built around 1800 by the British resident, Major Gore Ouseley, as a hunting lodge for his friend, the Nawab Saadat Ali Khan. It is now a ruin but still immensely grand: the architecture is based on Seaton Delaval Hall, Sir John Vanbrugh’s Northumbrian masterpiece. In the autumn of 1857, the house was taken by rebels but retaken by troops under Sir Colin Campbell. It must have been considerably damaged then, though contemporary photographs suggest it was not reduced to its present ruined state until later in the century. Major General Sir Henry Havelock, reliever of Cawnpore (now Kanpur), died here on 24 November, possibly of dysentery. (His statue by William Behnes is on the south-easterly plinth in Trafalgar Square.)

The most important ruin associated with the siege of Lucknow (from 30 May to 27 November 1857) is the former Residency, a beautiful 18th-century structure in a handsome park surrounded by other buildings dating from the late 18th century. The term “Residency” initially applied to the house of the British Resident; fine buildings nearby were inhabited by other officials. The siege reduced nearly all the buildings in this complex, now known collectively as the Residency, to ruin. Query: why didn’t the British rebuild them? And why, later, didn’t the Indians demolish them? It is now a well kept memorial to a terrible moment in India’s history.

The compound is entered by the Bailey Guard gate, overlooked by Dr Fayrer’s house (named after its early 19th-century resident surgeon and used as a defensive position and hospital during the Mutiny). His house is elegant even in its decay with its spacious facade of arched openings. Nearby are the remains of the two-storey Banqueting Hall, a school and post office. St Mary’s Church stands nearby in a graveyard that holds over 2,000 of those killed in the siege. In the Residency building — guarded by a large iron cannon, possibly the model for the one described by Kipling in the opening of Kim as standing in the fort at Lahore — is an exhibition recounting the siege and stories of some of those involved.

One of Lucknow’s most impressive sights is a complex that incorporates the 18th-century mosque Bara Imambara (pictured). With its mighty Mughal entrance gate, the Rumi Darwaza, and the mosque’s domes and minarets, it appeared when we passed it as a vast fantastical mauve silhouette in the afternoon haze with an orange sun hovering behind it. Our actual visit took place in brighter afternoon light. Bara Imambara was built in plastered brick by the Nawab of Awadh in 1784 as a Shia shrine, a colossal pillared hall, which, it is claimed, has the world’s largest unsupported roof. It is 50m long, 15m high, with arcaded floors above containing a famous labyrinth of small rooms full of what seemed to our Western eyes like ornate Victorian bric-a-brac. A long flight of steps descends to the vast courtyard where Muslims gather each year for Muharram, with the adjacent mosque with three domes and two handsome minarets at right-angles to the facade.

Not far off is Husainabad Clock Tower, built in 1881 to greet the new Lieutenant-Governor of the North-Western Provinces and Chief Commissioner of Oudh, Sir George Couper. This eminently Victorian structure is sufficiently slender and tall, at 67m, to possess the elegance of a fine minaret although it is touted in the guidebooks as a replica of Big Ben, which it in no way resembles. It overlooks a lake and the arcaded facade of the Portrait Gallery, which displays portraits of an august assemblage of Indian dignitaries of the last 200 years.

In the bus, as we approached Kanpur, a local guide summarised the terrible events of the 1857 Siege of Cawnpore in a clear, admirably dispassionate way. We heard about the betrayal of the British by Nana Sahib who had given his word that he would give them a safe passage to Allahabad but instead had the men massacred as they were about to embark at the jetty, then had the women and children slaughtered, throwing their dismembered remains down a well. The Bibighar, the house where the women had been confined, no longer exists; a public park spreads out, green and pleasant, in its place. All Souls’ Memorial Church, built from 1862 to 1875 to designs by Walter Granville and now called Kanpur Memorial Church, has a campanile and, architecturally, is consistently Lombard Gothic in style (pictured, above left).

The church has an apse lined with stone panels listing all victims of the massacre. In the churchyard is a screen with names round a large statue by sculptor Carlo Marochetti of an angel bearing crossed palms (pictured, bottom right, page 12 ). (By coincidence Marochetti was a friend of Lutyens’s father.) A tablet in the church commemorating three casualties — Philip Hayes Jackson and his wife Amelia and her brother Ralph Blythe Cooke — has an inscription quoting: “Vengeance is mine, I will repay, saith the Lord”. The British indeed took pretty unpleasant revenge.

Agra – The Taj Mahal, The Red Fort and Sikandra, 16 November

By Rebecca Lilley

Today we arrived in Agra — home to the Taj Mahal, built by Mughal emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal, who died giving birth to their 14th child in 1631 (pictured). One of the recognised jewels in the crown of northern India, it is a much more touristy area than we had previously visited.

I had not appreciated before that the main memorial was behind a complex of buildings forming gateways on each side of a central courtyard. The gateways were made of rich red sandstone in sharp contrast to the Taj Mahal’s iconic white marble. It was deeply emotional to see the evidence of so much love and grief contained within a single building. The water rills and fountains created a

serene foreground to it. There was little time for quiet reflection on our busy schedule but, after walking through and around the marble building inlaid with sumptuous gemstones, I felt I’d glimpsed the powerful emotions it surely arouses in all who visit it.

After a short drive to the Red Fort — named after its red sandstone walls — we entered this monolithic complex behind the impressive, defendable gateway. It was a great surprise to me that the fort, also known as Agra Fort, was not one large building but a town in its own right, with many buildings of all shapes and sizes. It would have been easy enough to spend an entire day there; instead, our guide Sharad pointed out some of its highlights. The Shish Mahal (1631), also part of Agra Fort, built by a Mughal emperor and studded with sparkling glass mosaic on walls and floors, was a particular favourite of mine. This was helped by the glimmer of sun when it occasionally broke free of the smog. Indeed, despite the smog it was a gloriously bright day, especially when we were in the well-maintained gardens of the fort with their box hedging and excitable stripey palm squirrels.

After a delicious lunch at restaurant Pinch of Spice, our coach driver took us to the walled gardens of Sikandra, created in 1613. Bearing similarities to the Taj Mahal, they contain the mausoleum to emperor Akba the Great. The pathways between its buildings are raised and contain water rills. Symbolic of water, yogurt, wine and honey, these are often found in Indian water gardens. Lower down were fields with animals, including deer, monkeys, birds and more squirrels. The buildings, each inlaid with intricate semi-precious stone mosaics, were very photogenic. The buildings were of the same red sandstone as that of the Red Fort and gateways at the Taj Mahal, and the mausoleum was situated in the centre of the gardens. Unlike the tourist-filled Taj Mahal, the gardens were peaceful: one felt relaxed wandering through their seemingly endless quadrants.

New Delhi, 17 November

By Rebecca Lilley

New Delhi — the pinnacle of Lutyens’s works in India and surely the main highlight of the tour. For me, the entire trip had been leading up to this. Our experiences of Mughal, Hindu and Buddhist buildings had taught us about the precedents that Lutyens had seen on his travels in India and incorporated in his designs at the new capital of Delhi.

With kind permission from Northern Railways, we were given access to the Lutyens-designed Baroda House, home of the Maharajah of Baroda, once much altered to accommodate Northern Railways’ offices. Its grand central domed circular space had been carved up into several storeys. On the first floor was a conference room that had cleverly been fitted under the dome. From the outside, the building remains largely as originally designed, complete with its gate lodges reminiscent of Lutyens’s pavilions at Serre Road Cemetery No2 in France.

In the afternoon, we visited Rashtrapati Bhavan. In my wildest dreams, I could not imagine the beauty and complexity of Lutyens’s genius here. Each room was a joy to behold. I would have liked to have seen more examples of Lutyens’s furniture but we only saw a few pieces because access to the building was restricted. One highlight for me was the library with its original built-in bookcases and new freestanding copies. Some of the verandas, which ran around the outside of the building, have been enclosed. These were originally designed to be open to help draw cool air into the building and create a shaded walkway.

Later we were invited to attend the Silver Trumpet Ceremony in Rashtrapati Bhavan’s forecourt, of which more later. Earlier in the day, we had been fascinated to see four soldiers dressed in immaculate white trousers and polo shirts, standing on a large wooden railway sleeper pulled along by a small tractor, smoothing down the red-sand forecourt in preparation for the event. After lunch, we were whisked off in golf buggies for a brief tour of the Presidential Estate and then took our seats to watch the Silver Trumpet Ceremony, as John Comins describes below.

Our last stop of the day was Bikaner House where we spent the evening with Malvika Singh, a longstanding friend of The Lutyens Trust and author of the book, New Delhi: Making of a Capital. Malvika had arranged a panel of people to speak to us about the conversion of the rundown former Maharajah’s Palace into a cultural centre, where art exhibitions and other cultural events now take place; and including a shop selling art, books and artefacts. Over a glass of champagne, she told us of her plans to restore the currently derelict, Lutyens-designed neighbourhood, Gole Market, and turn it into a museum. We enjoyed a tour of Bikaner House and took the opportunity to buy souvenirs of the building and books on Delhi. Malvika also made us honorary members of the house.

The Silver Trumpet Ceremony and the President’s Bodyguard, New Delhi, 17 November

By John Comins

An incidental pleasure of any visit to India is to appreciate how, over centuries, the country has adapted and retained customs of alien origin. We were privileged to be invited (see leaflet, left), to witness such a one in the forecourt of Rashtrapati Bhavan — the Silver Trumpet ceremony performed by the President’s Bodyguard.

The President’s Bodyguard is an elite household cavalry regiment of the Indian Army founded by Governor-General Warren Hastings in 1773. Over its 245-year history — and in various incarnations — its role has been to escort and protect successive Governors-General, Viceroys and now Presidents of India. Today, each new President marks his appreciation of their service by presenting a silver trumpet and banner to the Bodyguard at a mounted parade.

All candidates for the Bodyguard must be over 6ft tall, expert horsemen and sport splendid moustaches. Blue and gold ceremonial turbans, red or white longcoats, white breeches, gleaming boots, sabres and lances comprise their striking outfits.

The parade was not dissimilar to Trooping the Colour with the mounted troops going through their various evolutions at the walk, trot and canter. The President gave a short address and made his presentation. A brass and pipe band accompanied the horses’ movements and a commentary in Hindi and English kept us fully informed of the proceedings.

The ceremony over, various formations of horses performed over jumps, in dressage and in the musical ride for which four different coloured uniforms were required. These manoeuvres were perfectly executed. To some, the high point was the extraordinary skill with which riders at full gallop retrieved trophies planted in the forecourt with, in succession, lance, sword and dagger. As the afternoon faded, we could absorb in detail the changing impressions of Lutyens’s great palace and, in the half-light, collected our thoughts about the richness of India’s architectural heritage. In our ears as we left were, appropriately enough, echoes of Auld Lang Syne sung in Hindi.

Jaipur House and All India Memorial Arch, George V Memorial Canopy and the Great Place, 18 November

By Rebecca Lilley

Other highlights during the following days included a brief visit to Jaipur House, designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield in 1936 and now the National Gallery of Modern Art, a drive down Sikander Road with its fine examples of 20th-century bungalows and a walking tour of Lutyens’s King George V Memorial Canopy (pictured, left) and All India Memorial Arch (India Gate), the form and scale of which were stunning and brought tears to my eyes.

After this we alighted at Lutyens’s Great Place. Rather surreally, we first visited what must be the most beautiful public convenience on the planet (pictured). Subterranean and designed by Lutyens, it has a fountain similar to the one at Government House, Barrackpore. Its male and female loos were sadly bereft of their original porcelain fittings. Resurfacing, we walked up the Rajpath (formerly Kings Way) to the slope which caused the well-documented dispute between Baker and Lutyens, where Lutyens said he had met his “Bakerloo” (pictured, below). Passing Baker’s Secretariats and seeing Lutyens’s masterpiece reappear over Raisina Hill, you could clearly feel their powerful presence. It made me think it was no wonder that Lady Emily finally said she understood Lutyens’s genius with his New Delhi creation.

Old Delhi, 18 & 19 November

By Andrew Wilton

Delhi consists of several cities — built by different rulers at different times — each with a distinct character that deserves extensive exploration. We could only look at some highlights.

The first was the ancient group of religious buildings (pictured) around the famous Qutb Minar minaret, which soars with its subtly coloured scalloped fluting 73m above the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque, India’s oldest mosque, built in the 1190s. Here spacious quadrangles are constructed in the classic Hindu manner with columns built of separate blocks, distinctively ornamented, supporting straight lintels and shallow domes on squinches. We amused ourselves counting the carved bell motifs on columns and capitals, an inspiration for some of Lutyens’s decoration at Rashtrapati Bhavan.

Close under the minaret is the cubic south gateway to the mosque, of 1311, one of the most perfect pre-Mughal buildings in the country. (We had already seen a fine example — the tomb of Sher Shah Suri at Sasaram.) This gateway, the Alai Darwaza, is of dark red sandstone dressed with white marble, its sides pierced by high cusped arches (the first arches built in India) and windows filled with white-traceried jalis (latticed screens). Its dark interior was a fine place for schoolboys to test the echo. This happened to be a holiday weekend and the whole site was thronged with schoolchildren.

Back in Old Delhi’s maze-like centre, cycle rickshaws took us through dark, congested narrow streets to the teeming market Chandni Chowk and on to The Red Fort, which overlooks the river Yamuna. Founded in 1639 by Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, the fort occupies more space than The Red Fort at Agra, but after the Mutiny most of its buildings were razed by the British, so much of the interior is open space. The surviving pavilions flank the high bank of the river and lawns dotted with large trees. The site is organised as a vast garden with watercourses running across it, and water is an important element in the buildings themselves. Fine white marble fountains have lotus-patterned basins and intricately curling edges, all intended to make an exquisite play of water. It was unfortunate that, although we were there soon after the rains, these channels and fountains were dry. In the white marble Khas Mahal — once the emperor’s apartment — is a ravishing filigree screen incorporating the scales of justice in an otherwise abstract or floral design. It was saddening to see that this delicate creation has undergone severe damage in recent years.

The geometrical calm of the green spaces that extend between the fort and 19th-century garrison buildings also pervades the Mughal gardens that surround Humayun’s tomb (pictured, left). This was built in 1570 to the designs of Mirak Mirza Ghiyas and his son, Sayyid Muhammad, at the order of the empress Bega Begum, and is a crucial precursor to the Taj Mahal. Constructed of familiar red sandstone with white dressings, it deploys the Mughal square format — with a central dome and corner chattris on a high arcaded plinth — on such a grand scale and so authoritatively that it seems to say all that needs to be said. Only the Taj outshines it.

Old Delhi possesses another almost perfect building in red-and-white stone: the Jama Masjid or Friday Mosque. With elegantly striped minarets, it is finer than the rather similar mosque in Agra, though nowadays it is organised for tourism in an obtrusive way with roped stanchions indicating where one can and cannot walk.

We were taken by bus to the north of the old city to see St James’s Church, finished in 1838 by Colonel James Skinner, who is buried at the altar step, to his own designs. Skinner was famously excluded from the army owing to his mixed blood; his cavalry regiment, Skinner’s Horse, was established in 1803 and distinguished itself in many engagements. St James’s was the official church of the Delhi Government until Henry Medd’s Anglican Cathedral Church of the Redemption was built between 1927 and 1935.

Close by is the Dara Shikoh Library in the archaeology department at Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University in Delhi. It is named after a son of Shah Jahan, and the building partly dates back to the 17th century. In 1803 it was home of the British Resident, David Ochterlony, who added the neoclassical facade, a regular Ionic colonnade with tall windows between the columns — regular, that is, except for an unexpected wriggle out of alignment of the central three bays with the neighbouring bays on each side slightly chamfered, giving the effect of an error in measurement at the time of its construction. It is in the process of restoration.

An intrepid group of us then rode to a huge maidan on the outskirts of the city in search of Coronation Park. To our consternation we found hundreds of acres of land covered in brightly coloured tents and huge crowds accompanied by deafening amplified announcements, prayers and music; a Sikh festival was underway, we learned. To find Coronation Park seemed a hopeless task in such a vast fair. But our admirably persevering driver found us tuk-tuks which conveyed us through the mêlée to the park where we wandered freely. Here are many great public statues of the Raj, later grouped around an obelisk that commemorates the mass assembly, the Delhi Durbar of 1911. This has a plaque that records: “Here on the 12th day of December 1911, His Imperial Majesty King George V Emperor of India accompanied by the Queen Empress in solemn Durbar announced in person to the Governors Princes and Peoples of India his Coronation celebrated in England on the 22nd day of June 1911 and received from them their dutiful homage and allegiance”.

Apart from one or two heavily bemedalled busts, the statues are tall, over life-size, full-length sculptures of George V, Lords Curzon, Willingdon and Hardinge and other viceroys. The format is consistent in all of them: a high plinth, with the subject in full ceremonial robes. The one of the king originally stood in Lutyens’s high chattri before the India Gate on the Rajpath. An inscription or coat of arms occupies the front of each plinth. It was reassuring to see these sculptures – by leading artists, including Charles Sargeant Jagger – looking dignified if isolated in a reasonably well-kept garden. But there was one disturbing detail — each statue’s nose had been brutally and, it seemed, wantonly smashed off, evidently quite recently. It’s worth noting that a striking white marble statue from this group, of Rufus Isaacs by Jagger, is to be seen in Eldon Square in Reading, Berkshire, where it is almost shockingly grand and overscaled for its situation.

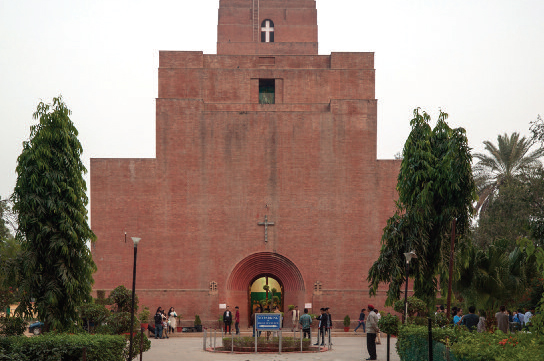

Our day ended at AG Shoosmith’s monumental Garrison Church, St Martin’s (pictured, right), which, intended as a fortress in the event of another mutiny, rises up like a daunting power station. Despite its bully-boy scale and uncompromising exterior, it is in fact subtle, with much carefully considered detail in the interior, including elegant, very Lutyens-esque doorways on either side of the chancel. Shoosmith, in addition to the Garrison Church, was responsible for the guesthouse Lady Hardinge Sarai, opposite New Delhi train station. It was built in 1931 in a more recognisable Art Deco style and is now the Lady Hardinge Medical College. That year, he returned to England, where he died in 1974, having built nothing more.

A number of our party, about six, clambered about high up on the church’s roof until it was dark. Rebecca, one of these, described this exploration thus: “It was too much of a good opportunity to miss when the church warden invited us to climb the church staircases, corridors, domes and shafts to reach close to the top of the building and take in the magnificent views of Delhi that the tower offered. We enjoyed the promised views as the sun set.” After these adventures, we returned to our hotel to change for our farewell dinner at the legendary Imperial Hotel that marked the end of the main tour.

20 November

After this last stage of the main tour, 16 of us stayed on for the extension of the tour (until 26 November) which started with a visit to Baker’s Parliament building in New Delhi and then continued on to Amritsar, Chandigarh and Shimla. Highlights of this are described below.

Photo courtesy of Lok Sabha Secretariat

Herbert Baker’s Parliament Building, New Delhi, 20 November

By Rebecca Lilley

The following morning Anita Singh had arranged for our small extension group to visit Baker’s Parliament Building (pictured). Our hosts welcomed us and a specially arranged panel discussed the issues surrounding the need for ever more space at Parliament, and the conservation of the important building. This was followed by an interesting guided tour, including the newly built library and Parliament Museum. It was fascinating to see the inspiration drawn from Baker’s building in the library’s design, and equally the innovative ways in which the original building was being altered to improve its infrastructure. For example, the maze of pipework under the floors is being uncovered and super-insulated cables laid for internet access throughout.

It was with mixed feelings that we left Delhi, sad to leave behind such an important and inspiring city yet excited at the prospect of what was to come.

Amritsar, 21 November

By Stephen Williams

Having left Delhi the previous afternoon on a long, exhausting train journey and endured choking smog for the past two weeks, arriving at this old city’s gates in the early morning was a great relief. Amritsar is the Sikhs’ capital and guards its holiest shrines. It proved to be one of our visit’s most riveting highlights. Historically it is known as Rāmdāspur and colloquially as Ambarsar.

We had first encountered the self-confident, welcoming character of Sikhism, with its passionate sense of community and history, in Patna. Here we had visited the Takht Sri Patna Sahib (or Harmandar Sahib) – an interior of which is pictured left — a place of worship for Sikhs, also called a Gurdwara. Its gleaming white buildings shimmering beneath the blue sky formed a wonderful backdrop to the multicoloured dastaars or pagris (turbans) of the elegant bearded Sikh men.

This Gurdwara was founded in the early 19th century but the current shrine building only dates back to the 1950s. For followers of Sikhism, Patna — as the birthplace of Guru Gobind Singh, the 10th Sikh Guru in 1666, and with its links to Buddha — ranks second to Amritsar in importance. Our visit there was an astonishing prelude to what we were to see in Amritsar.

Amritsar, in the relatively wealthy state of Punjab, offered a mix of shining brilliance and neglectful if magnificent decay. Passing through one gate in the walls circling the old city — founded in 1577 by 4th Sikh guru, Guru Ram Das — we came to the late 19th-century Town Hall with its gracious classical redbrick buildings formed around a magnificent courtyard. These buildings of the Raj had recently been restored, significantly to create a new “Partition Museum”, since the site stood witness to the unrest in the Punjab after both the Jallianwalla Bagh Massacre and Partition.

Beyond this was a public space with one of several imposing statues of Maharajah Ranjit Singh (1780-1839) riding his stallion. Known as the “Lion of Punjab”, he expelled the Afghans and put in place wide-ranging reforms that secured the future and prosperity of the Sikhs. He signified well the fiercely courageous nature of the Sikhs combined with the gentleness of their religion.

We first visited the Gurdwara Saragarhi. This small intricately detailed white monument with a central dome surrounded by turrets, now uncomfortably hemmed in on two sides by tall modern buildings, commemorates the 21 Sikh soldiers from the 36th Sikhs infantry regiment who died in the Battle of Saragarhi in 1897. Two stern attendants would not allow access to the interior of the building, which symbolised the Sikhs’ pride in their history of defending their religion. Overlooked by another mounted statue of the “Lion of Punjab” atop a large tiered fountain, we were welcomed and saluted by a character in full traditional dress, including ceremonial dagger and axe.

We then entered the old city with its narrow streets crowded by a wonderful melange of old houses, mansions, apartments and shops. This was the most atmospheric street walk we experienced in India. In the 1500s, Guru Ram Das invited 52 trader families to settle in Amritsar and many magnificent mansions were built. Today the buildings in the old city, dating mostly from the 18th and 19th centuries when Amritsar was the centre of the Sikh empire, are very dilapidated and under threat of being swept away by unrestrained modern development.

We first visited the fort, Qila Ahluwalia, which once belonged to Ahluwalia Misl whose famous leader, Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, played a vital role in repelling foreign invasions during the 18th century. This large square, with tall four or five-storey balcony-access buildings, was very imposing but in poor condition with some remnants of its important past visible thanks to the many alterations made to it after it was sold to Marwari families in 1900.

Leaving Qila Ahluwalia and joining its surrounding lanes, we saw many run-down, mostly 18th and 19th-century homes and shops of wealthy merchants in Indian and Colonial styles. Looking upwards, the eye was beguiled by the intricate decoration of the wooden galleries. Enclosed bay windows jutted out over the streets. These balconies or jharokhas are delicately formed in a tracery of carved and interlocking carpentry. Often seen in Indian architecture, in Amritsar we saw exceptionally inventive and refined examples. In these buildings with their old paintwork we saw magnificent paintings of traditional Indian scenes that were now so faded as to have almost disappeared.

The life in the lanes and fabulous colours and textures of the old doors here create an extraordinary atmosphere. Green and blue doors, most of them beautiful, dominated the houses. Although now severely worn and weathered, some buildings often had intricate, traditionally carved stone and stucco-work panelling.

The street life was wonderfully alive. As we entered Jalebiwala Chowk, some of our group bought the famous jalebi from a street stall. Men sang as they pushed their bicycles through the lanes selling vegetables. Tricycle rickshaws wove their way between jostling pedestrians, mopeds, motorbikes and sometimes cars.

In some buildings, we found small temples and religious hostels jostling next to shops, hidden away. The most extraordinary temple we visited was Udasin Ashram Akhara Sangawala, established in 1771. This practises the Udasi or Udasin religion, an ascetic sect following sampradaya (tradition), which considers itself a denomination of Sikhism. It focuses on the teachings of its founder, Sri Chand (1494-1629), son of Guru Nanak, founder and first guru of Sikhism who passed over his son as his successor. Sunken and reached by a flight of stairs, the temple blazed with garish decoration. Unlike the monotheistic beliefs of Sikhism, Udasi had reverted to its Hindu roots following many gods. Again, unlike the Sikh temples, it had a series of claustrophobic dark rooms leading to the main temple in a small cave within a boulder. Having crawled through a narrow tunnel to reach it, we discovered that only a few could sit in its cramped space. A small group did accompany our Sikh guide into the cave, where he regaled them with some interesting if tantric views. In contrast to the light, open, white and gold Sikh temples we had seen, this temple bore heavily down on you in its sunken location.

Moving on near to the end of the Bartan Bazaar, we came to a junction where, in the middle of a road, was the equally strange and small but tranquil Baba Bohar temple through which grows the centuries-old banyan tree. Here individuals made offerings and prayed to a small shrine to be healed.

Soon after, we came to a small doorway off a lane. Here was the Chitta Akhara Temple, marked by highly decorated wooden panelling. We passed down a short passageway to reach a colourful complex at the other end — a hostel established in 1781 for spiritual seekers and saints. Rooms led off its central courtyard and, on the first floor, there was a cantilevered wooden gallery.

Finally we left the old city’s narrow lanes and, after covering our heads with an orange cloth and washing our feet, we entered the Golden Temple complex, also known as the “abode of God” (pictured), through the main northern gate, the Darshani Darwaza. A breathtaking view of a glistening blue lake — in the middle of which sat the golden domed central shrine (Harmandir Sahib or Temple of God) — opened up beneath us. Seemingly floating on top of a pool of clear blue water, the Golden Temple was linked by a covered causeway to the wide marble path called the Parikrama, which was surrounded by the stretch of water, Amrit Sarovar, meaning pool of nectar. The Golden Temple, also known as Sri Harmandir Sahib, is relatively modest in size with small windows and a dome, expressing perhaps the lack of pomposity and grandeur that other religions wish to express in their important buildings. Under the beating sun and clear blue sky, the gold-covered marble building shimmered in its watery setting. Walking along the Parikrama, the eye was inevitably drawn back constantly to the golden Sri Harmandir Sahib. Unfortunately, a long queue of pilgrims was slowly filing along the bridge entering beneath the Darshani Deorhi pavilion, so we reluctantly did not have time to enter the shrine. Three musicians played and sang traditional holy music as the pilgrims joined the end of the queue.

Opposite the Darshani Deorhi, and set back and high up, was the white marble Sri Akal Takht Sahib. This seat of power symbolises the temporal authority of God and is only second in holiness to the Golden Temple, which symbolises God’s spiritual power.

Although it is a place of great holiness to Sikhs, we were generously welcomed and, strolling slowly along the Parikrama, we mingled with the crowds on their pilgrimage. Sikhs were ritually bathing in the water, using chains to haul themselves back onto the pavement. Ladies also bathed but in a small, screened-off area of the water. Many sat on the pavement in the shade or at the water’s edge while others watched the koi carp swimming in it. In line with the tradition of welcoming all, the Temple offers free food to all its visitors at the community kitchen Garu ka Langar in a gigantic hall seating 3,000 where volunteers serve food and drink. Food preparation, serving and washing up are carried out with impressive speed and efficiency. This is apparently the world’s largest dining hall.

Even with the crowds — the Golden Temple welcomes 100,000 people a day, all freely chattering — the Gurdwara retained an elegance and poise, creating a truly tranquil and magical setting.

We also visited a sadder place before we left — the Jallianwala Bagh. A green park where people relax after a visit to the Gurdwara, it is the site of an infamous massacre in 1919. Here Colonel Reginald Dyer ordered soldiers to open fire for 10 minutes on a crowd of Sikhs, some of whom were protesting peacefully, until the soldiers ran out of ammunition. At the end of it, hundreds had died and thousands lay injured. This massacre is often seen as marking the beginning of the end of the British Empire. The park holds several memorials, including the bullet-marked wall where many died.

We walked down the narrow rather nondescript alley, along which the British forced the non-British to crawl with the threat of being shot. Two similarly violent events occurred almost 70 years later when the Indian Government was fighting Sikh militants who, in 1984, had barricaded themselves in the Golden Temple demanding independence. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered the army to put down the insurrection known as Operation Blue Star. This led to Gandhi being assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards and the desertion of many Sikhs from the army. The Golden Temple was badly damaged and some buildings demolished. And in 1987 the militants again took over the Temple, but this time Rajiv Gandhi used subtler if still violent means to overthrow the militants and undermine their credibility with the Sikh community. The temple has only finally been restored to its former magnificence in the past year or so. To learn more about the events, you can read the chapter devoted to them in Mark Tully’s excellent book, No Full Stops in India.

This was a poignant way to leave Amritsar and, that afternoon, we travelled to the gated border crossing between India and Pakistan at Wagah, 22km from Lahore. This reminded us of the third and greatest event of the 20th century in the Punjab — the Partition in 1947. We walked the last kilometre to the border with crowds of Indians coming to watch the “lowering of the flags”, a daily military practice carried out since 1959 by India’s Border Security Force and Pakistan’s Pakistan Rangers. This ceremony was watched by Indians and Pakistanis from stadia on either side of the gated border post. We entered one large stadium to the sound of music and singing. Here young Indians seemed to be having a party with many watching and cheering from their tiered seating. When the ceremony started, Indian soldiers appeared dressed in brown uniforms with bright red sashes and extravagant bright red headdresses, making them look like proud peacocks. On the Pakistani side, the border guards wore slightly more sombre dark green but still sported red sashes and peacock headdress. The Pakistani onlookers were also more subdued in their celebration of the event. Dressed in colourful uniforms, the guards on both sides marched up and down almost in tandem with elaborate and rapid dance-like manoeuvres. All guards were well over 6ft tall to ensure neither side was overshadowed. Our lasting impression was of the stern, angry look of defiance on the rival guards’ faces. This symbol of the two countries’ rivalry perhaps channels and controls their real aggression towards each other.

At the end of a tiring day, we returned on the long straight walk away from the border, jostled by the large crowd, which gave us an inkling perhaps of how it may have felt for so many of those who walked exhausted along these roads in 1947.

Kapurthala, Patiala, Chandigargh and Shimla-Kalka Toy Train

By Graham O’Neil

Leaving Amritsar we headed south-eastward in our exploration of the Punjab, visiting the capitals of two princely states, Kapurthala and Patiala.

The key influence on the architectural development of Kapurthala was Maharajah Jagatjit Singh (1872 -1949). He was enamoured of all things European, including of Spanish flamenco dancer and singer Anita Delgado, who became Maharani of Kapurthala. He built a splendid French-style chateau, a Spanish villa and magnificent Moorish Mosque based on the Grand Mosque of Marrakesh. We visited the Moorish Mosque, designed by French architect Monsieur M Manteaux and built between 1927 and 1930. Parts of the exquisite interior are attributed to the artists at Mayo School of Art, Lahore.