Exterior of Castle Drogo with scaffolding © Rebecca Lilley

Interior of the castle with part of the ceiling revealed © Rebecca Lilley

Jill Smallcombe in front of the Char de Triomphe tapestry © Rebecca Lilley

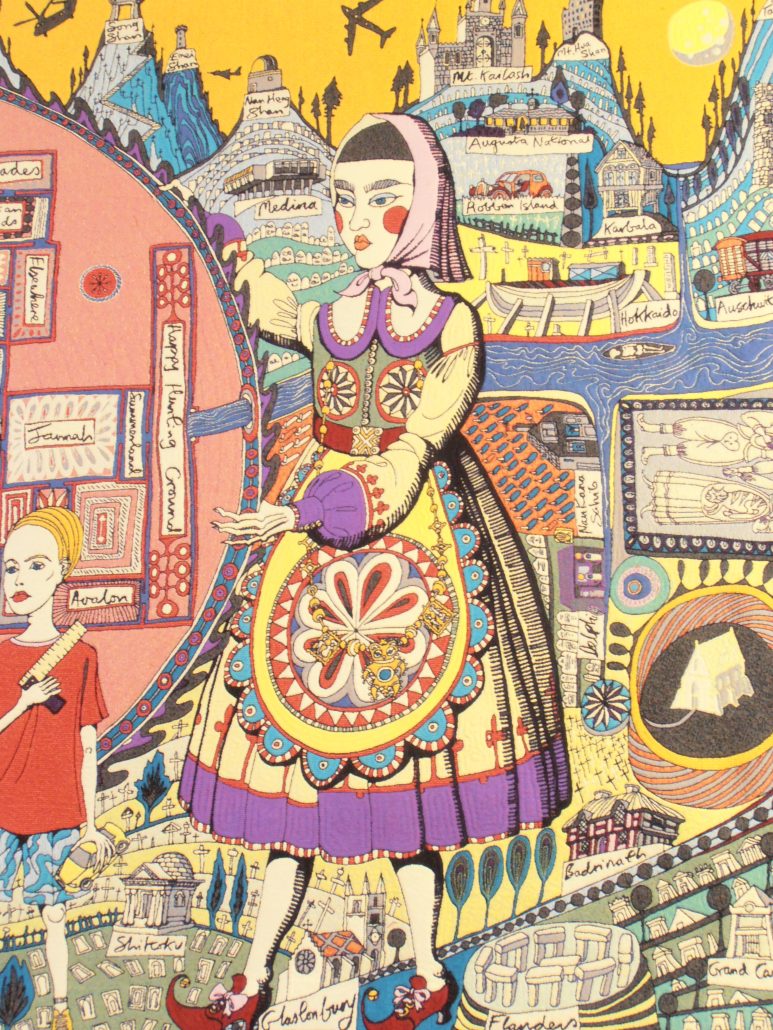

Detail of Grayson Perry’s tapestry Map of Truths and Beliefs © Rebecca Lilley

Rebecca and Paula Clarke in the castle’s Activity Hut © Rebecca Lilley

Saving Castle Drogo – My Involvement in this Important Restoration Project

By Rebecca Lilley (Summer 2016)

In September 2011, I visited Castle Drogo for the first time. I’d just graduated with an architecture degree from the University of Kent, and knew little about Britain’s great architects, having learnt more about their European 20th-century counterparts, such as Mies van der Rohe. The Saving Castle Drogo restoration project hadn’t started, so I took the building in, as many do, as a glimpse of the past occupants of this great work of Edwin Lutyens.

Last December, after 17 months working for the Lutyens Trust, I wanted to know more and wrote to Bryher Mason, Drogo’s House and Collections Manager, asking if I could spend two weeks on the project with her team. She promptly agreed and I jumped at the chance.

I arrived at the castle on Sunday, 21 February. Although it was a misty, overcast day, the castle loomed out of the fog, almost entirely covered in scaffolding and a great white tent. I’d read the project’s progress updates in the Spring 2015 Newsletter, but hadn’t been prepared for how much the castle had changed since my previous visit. The great entrance door, complete with stone lion above it, was obstructed by scaffolding, so I was admitted through a side door. It was not until Monday morning that I got a clearer picture of the sheer extent of the works throughout the castle.

It was very interesting to hear about the current and ongoing installations in the corridors and rooms in place of normal furnishings, which are mostly in storage. Despite the extensive works to the outside of the building, I hadn’t imagined the inside would be affected so much. I’d realised the damp would have caused many items to be removed from display, and that certain areas of the castle were off-limits. But I didn’t expect it to be shrouded in darkness; what little light that penetrated the scaffolding was obscured further by the plywood shuttering encasing the grand bay windows and many smaller ones, too. The grand corridors, usually majestic in scale, were mere stunted creatures, their ceilings concealed by

multiple plywood walls reaching right into the vaulted ceilings.

I was amazed by the sheer enthusiasm the staff and volunteers showed despite months and, in some cases, years spent behind the scaffolding. They were at once busy scurrying about doing their own work and happy to help other departments in readiness for when Drogo reopened in the spring at the end of my stay.

While at Drogo, I spent time in various departments. On the first day, I worked with Jill Smallcombe, an artist and the castle’s Training and Skills Coordinator. She had arranged for the hire of the Grayson Perry tapestry Map of Truths and Beliefs, and was organising an exhibition to take place in the dining room, featuring another Perry print and the 17th-century Gobelin tapestry, the Char de Triomphe, which is part of the castle’s collection. It was my pleasure to assist in the preparation for moving the latter and for the hanging of the Perry tapestry.

I also spent time with Paula Clarke, Community Engagement Officer, marshalling 150 schoolchildren on their one-and-a-half mile run around the castle estate. On day three I had an amazing full tour of the castle — including the private family apartments and maze-like basement levels where electricity generated by a turbine in the river below originally entered the building — courtesy of Tony Sawyer from the house team. A highlight of the day was being able to unwrap the castle’s 1906 mechanical dolls’ house in the Arts and Crafts style — complete with working light switches and plumbing — ready for its deep clean.

I was also given a chance to inspect the building works and attend meetings with the contractors. Kitted out in steel-capped boots, hi-vis jacket and hard hat, I was led round the scaffolding by Project Manager Tim Cambourne and Clerk of Works Wes Key. It was only from the top of it that you could appreciate the sheer scale of the project. The roof is divided into a suite of room-like spaces, and it was gratifying to see the repairs here were almost complete on the central and south sides. In fact, the current phase of works was nearing completion, and the scaffolding was being dropped in places. Walking along a gorge near the castle, I was elated to catch my first glimpse of the newly uncovered South Tower, which shone in the spring light, having been intensively cleaned.

Huge excitement was had by all when, on Thursday, Bryher dashed into the office to tell us all that the protection around the bay windows in the entrance hall had been removed and that natural light was pouring into the space for the first time in around two and a half years. During the rest of my stay, the fireplace in the hall was opened up and the Lutyens cast-iron lamps unwrapped and switched on. The protection doors in the nursery corridors were moved, allowing the space’s true scale to become visible, and the chapel was deep-cleaned. In the weeks to come, if only temporarily, I was told the castle would at last be revealed from under the scaffolding, and guests would be able to see a clear line between the cleaned and repaired south side and the as yet untouched north side before work on the next phase began.

I am truly grateful to Bryher and the Drogo team for allowing me to be part of their world for two weeks. Their hard work on the Saving Castle Drogo project has been a true inspiration, and I look forward to visiting again in the future.