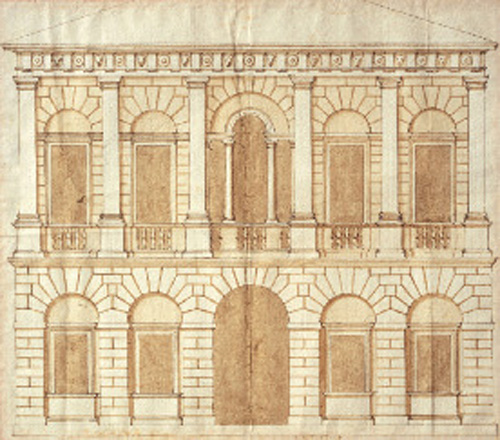

Design for a palace by Andrea Palladio (c 1540s) © RIBA Collections

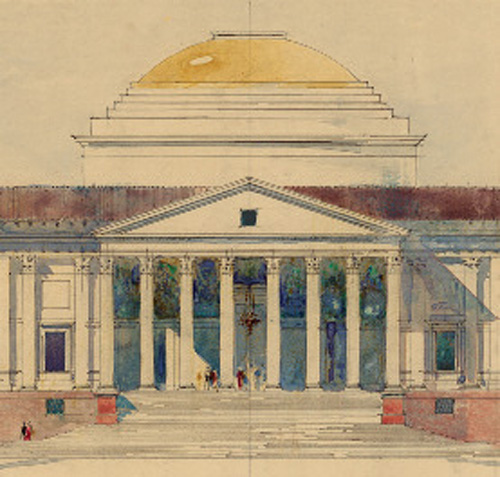

An original sketch for the Viceroy’s House, New Delhi by Edwin Lutyens, 1912 © RIBA Collections

Glashutte, Germany by Oswald Mathias Ungers, 1985 © Stefan Mueller

RIBA Exhibition Palladian Design: The Good, The Bad and The Unexpected

Reviewed by Margaret Richardson

As the press notes to this exhibition say, it “introduces Palladio’s design principles and explores how they have been interpreted, copied and reimagined across time and continents from his death in 1580 to the present day”.

It is divided into sections with clearly written introductory panels. The first is called “Andrea Palladio. Reinventing Antiquity: his revolutionary accomplishment was to reinterpret antiquity for his own time”. It is an amazing display that includes Palladio’s I Quattro Libri Dell’Architettura of 1570, the most influential architectural treatise of all time, and four original Palladio drawings from the RIBA’s Burlington Devonshire Collection. The drawings, originally collected by Inigo Jones in Italy, are particularly beautiful.

The next section, “The Rise of Anglo-Palladianism”, shows drawings by Jones, Sir Roger Pratt, John Webb, Colen Campbell, Lord Burlington and William Kent. Then comes “Spreading the Word”, featuring different editions of I Quattro Libri, and, importantly, Giacomo Leoni’s first translation of it into English of 1715, which was very influential and especially popular in the American colonies. The other important books were Campbell’s Vitruvius Britannicus of 1717, Batty Langley’s The Builder’s Jewel of 1741 and Abraham Swan’s The British Architect of 1745.

From this point on, the exhibition shows many examples of architects bending the Palladian rules and introduces contemporary examples. For example, Allan Greenberg, who has written so much about Edwin Lutyens, is represented with his house Beechwoods in Connecticut of 1992 and Duncan G Stroik with his 1994 Villa Indiana at South Bend, Indiana, which is closely based on Palladio’s Villa Valmarana. Palladio’s exquisite design for it is hung close by.

The section on “Statement Architecture” demonstrates how Palladianism came to be favoured for government buildings at home and in the colonies. There is an immense perspective of Stormont in Belfast by Sir Arnold Thornely, completed in 1932, and a perspective of St John’s Church in Kolkata, its design based on James Gibbs’s model of St Martin-in-the Fields, displayed nearby. Lutyens’s first 1912 design for the Viceroy’s House is included in this section “conceived as an 18th-century Anglo-Palladian country house on an inflated scale, combining a Pantheon-like shallow dome with the expansive portico of Palladio’s unbuilt Villa Mocenigo”. The last two sections show fascinating examples of work by 20th-century architects where Palladianism is stripped to its essentials — work by Gunnar Asplund, Oswald Mathias ungers, Aldo Rossi, Caruso St John and others, which represent the “unexpected”.

Lutyens came to appreciate Palladio, as we know from his famous letter to Herbert Baker in 1903 in which he wrote, “In architecture Palladio is the game!! It is so big, few appreciate it now and it requires considerable training to value and realise it”. But we do not know if Lutyens owned a copy of I Quattro Libri himself. The remnants of his Office Library, listed in the 1981 Hayward Gallery exhibition catalogue, do not include a Palladio but include Langley’s City and Country Builder’s and Workman’s Treasury of Designs of 1740 (not the book shown in the exhibition). Two other Lutyens office copies of this book also exist and came to be known as the “Office Bible”.

This is a riveting exhibition, co-curated so well by Charles Hind and Vicky Wilson and displaying so many great treasures from the RIBA’s collections.

Palladian Design: The Good, the Bad and the unexpected is at The Architecture Gallery, RIBA, 66 Portland Place, London W1 until January 9, 2016.